Tillerson at State Boosts Exxon Immeasurably

When sanctions were placed on Russia, Exxon left behind the potential to produce billions of barrels of oil. Secretary of State appointee Rex Tillerson could be in a position to secure that prize for Exxon.

There’s no doubt that Rex Tillerson and Exxon’s executives and shareholders will profit from his nomination to Secretary of State. The only question is by how much.

After the nomination became news Monday morning, Exxon’s stock was up over 5% by Tuesday afternoon, making millions for Tillerson and fellow shareholders. But over the long term, tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars are at stake as the new Secretary of State holds sway over decisions that could reopen billions of barrels of Russian oil and trillions of cubic feet of gas to the company he has served his entire career.

Chart: Exxon shares up over 5% on Tuesday afternoon on news of Rex Tillerson’s Appointment – Source: Financial Times

Exxon is a Global Player

Exxon currently produces oil and gas in 22 countries. But it has exploration and development activities in a number of prospects and is expected to be producing in 36 countries by 2030. Those prospects are all over the globe. From Asia (China and Vietnam), to South America (Colombia, Guyana and Uruguay), to Africa (Mozambique, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Congo, Tanzania, Liberia) and even in Ukraine.

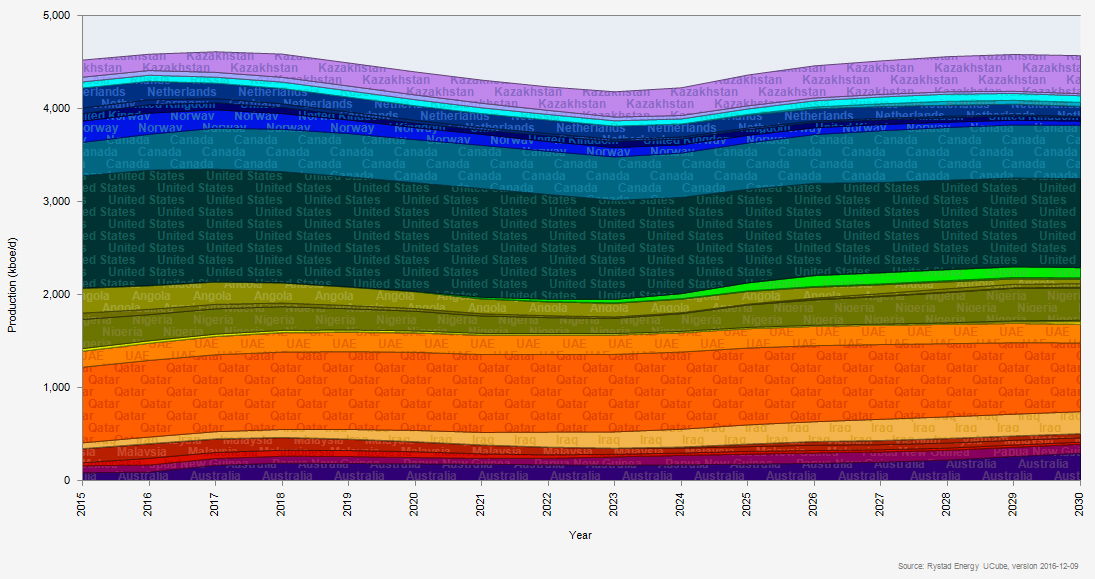

However, a large portion of its currently projected growth is expected to come from projects that are already producing in Kazakhstan, Iraq, Australia, Canada, Qatar and Nigeria, to name a few. Production in the United States is expected to shrink slightly.

Chart: Current Projections for Exxon Global Oil and Gas Production by Country (oil and gas in barrels of oil equivalent per day) Source: Rystad Energy AS

A Future Subject to Change

But this is a picture of the current outlook for Exxon. That outlook can change dramatically as a result of new oil and gas discoveries, new deals, mergers and acquisitions, and of course as a result of new geopolitical developments.

As has been widely discussed, there are few geopolitical developments that could be of greater benefit to Exxon than the lifting of sanctions on Russia.

In April 2012, Exxon signed a “Strategic Cooperation Agreement” with Russian oil giant Rosneft in a ceremony in Moscow attended by then Prime Minister and President-Elect Putin. There were three key areas in Russia specified in the agreement that sought to “bring together the resource potential of the Russian national oil company Rosneft with the project management expertise of the global energy leader ExxonMobil.”

On April 18th, Exxon investors gathered in the St. Regis in New York City to hear the details of the deal, and were played a video outlining the tremendous opportunities it promised.

In the video the three key areas of exploration and production were detailed. The first of these involved 31 million acres of the Kara Sea in the Russian Arctic. The resource potential was estimated at 85 billion barrels of oil equivalent. The audience was told: “Even partial confirmation of this potential will in effect create a new oil-producing province of global significance and will substantially increase the proven reserves and capitalization of both partners.” 1

At the time the area involved was compared to the North Sea. But by early 2013, the joint venture expanded to cover a total of 180 million acres in the Kara, Chukchi and Laptev seas, an area roughly six times the leased area in the Gulf of Mexico at the time, or larger than the state of Texas. Big prospects indeed.

In the summer of 2014, with the annexation of Crimea well underway, Exxon drilled its first exploration well in over 200 feet of water in the Kara Sea and in late 2014 announced that it had indeed found hydrocarbons (oil and/or gas). It capped the well and abandoned it for the winter season.

By September 2014, President Obama extended sanctions against Russia to include oil and gas exploration and the joint venture between Exxon and Rosneft was thereby frozen.

While Russia described the deal at the time as being worth $500 billion, nobody can really say what the potential value of the Exxon/Rosneft JV could have amounted to. Much depends on what lays below the Arctic seas controlled by Russia and what the cost of extracting and delivering that oil and gas would be compared with the prevailing global oil price. But it’s clear that the potential was (and still is) huge.

However, the Arctic was only one of three areas that were part of the deal. Acreage in the Russian Black Sea was also part of the deal as was access to tight oil formations in onshore areas that Rosneft was already operating in Western Siberia. Exxon would bring to these tight oil plays its experience with fracking in North America.

The Black Sea blocks were estimated to contain around 9 billion barrels of oil, while the potential resource in Western Siberia was estimated at around 13 billion barrels. Some experiments with fracking were already under way in Western Siberia and the initial results were said to be promising. Analysts at the meeting were encouraged that the production from fracking could begin generating revenue within a couple of years compared to the much longer term prospects of the offshore Arctic and Black Sea.

So with over 100 billion barrels estimated to be at stake, there is no doubt that the prospects in Russia currently being denied to Exxon due to sanctions are substantial and that the company would relish the chance to reenter the country.

Of course all of these potential resources should be left in the ground in order to maintain a chance to achieve climate goals as detailed in our ground breaking report, the Sky’s Limit. This is a goal that a U.S. Secretary of State should be striving to achieve. But recent remarks by Tillerson about the Russian deal indicate how keenly his company would like to return.

Back in March of this year, at Exxon’s annual ‘Analysts Meeting’ at the New York Stock Exchange, Tillerson was posed a “hypothetical question” by an analyst on what Exxon’s response would be to the lifting of sanctions on Russia. The analyst was wondering whether the abandoned projects in Russia would still be of interest in the current lower oil price environment. Tillerson was very clear that all three prospects were still highly attractive to Exxon.

“Yes, we would. We’d be interested in getting back to work. (…) Obviously, getting back to work, particularly in the Arctic, will take us a while, because we had to dismantle all of the capability and the infrastructure. (…) but we are very anxious to get back to work there. It’s a really interesting, exciting area. We are (also) very interested to get back to work in the deepwater Black Sea. We think there’s a — it’s a very prospective area as well. And then the onshore stuff and the tight oil — we would love to help them take a look at that, but we’ll just have to wait.”

Additionally,, he outlined how the Obama Administration continued to work with Exxon to make sure it did not lose its stake in Russia despite the sanctions. Tillerson said:

“I’ll tell you, we are in constant conversation with the US government around ensuring that we are able to protect our rights in Russia while we have to stand still, and they’ve been very supportive of that.

“So I’m thankful that they have never done anything to try and make the situation worse. In fact they’ve done things to help us hang on to the rights we have. We’ve been through sanctions in countries before, and that’s something governments have to work out. We would just like to make sure we can maintain our position, and when a new time comes, we are ready to go back to work.” 2

It would appear that with Tillerson as Secretary of State, Exxon’s keen interest in returning to Russia could become an interest shared by the Trump administration. The benefit to Tillerson and Exxon’s shareholders of a major foreign policy u-turn that ends sanctions on Russia is literally immeasurable at this time. But the conflict of interest is all too clear.

Transcripts from CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Factiva.

Transcripts from CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Factiva.