Unclear on the Concept: How Can the World Bank Group Lead on Climate Finance Without an Energy Strategy?

The World Bank Group is experiencing clear difficulties in synching its core lending and its energy strategy with climate goals, and the institution has taken steps that can easily be viewed as creating a conflict of interest. Given these difficulties and contradictions, the institution should focus on cleaning up its own act before making further forays into climate finance initiatives.

Oil Change International, BASIC South Initiative, Campagna per la riforma della Banca Mondiale (Italy), Friends of the Earth U.S., groundWork (South Africa), International Rivers, Sierra Club (U.S.), Urgewald (Germany), Vasudha Foundation (India)

Oil Change International, BASIC South Initiative, Campagna per la riforma della Banca Mondiale (Italy), Friends of the Earth U.S., groundWork (South Africa), International Rivers, Sierra Club (U.S.), Urgewald (Germany), Vasudha Foundation (India)

December 2011

Download the full report.

International climate negotiations highlight the need for a fundamental shift in energy production globally – towards a system of clean, climate-friendly energy choices. For developing countries, these clean choices must go hand in hand with development goals and reducing energy poverty. Fortunately, the costs of clean energy are increasingly competitive, and decentralized, renewable energy is often the most cost effective way to provide energy for the world’s energy poor.

In recent years, the World Bank Group (WBG) has become increasingly involved in international climate discussions, indicating that it wants to have a greater role in climate finance in developing countries. The WBG has acknowledged and rhetorically reinforced the need to address climate change impacts in order to achieve development goals going forward. Moving into the Conference of Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Durban, South Africa, the WBG has continued to push for a leadership role in climate finance through carbon offsetting schemes and carbon trading, the Climate Investment Funds, and the Green Climate Fund. This presence in climate finance continues even though many of the WBG’s decisions and self-appointed roles in climate initiatives continue to be challenged by developing countries and civil society.

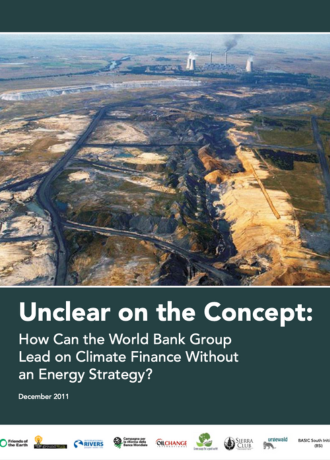

As a result of the institution’s continued support for dirty fossil fuel projects and its failure to approve a climate sensitive energy strategy, the WBG continues to finance unsustainable dirty energy choices that are harmful to the climate and lock developing countries into energy models that are both dangerous and expensive. In spite of its climate-friendly rhetoric, the WBG continues to disproportionately fund dirty energy projects within its core energy portfolio, with nearly half of energy lending – more than US$15 billion – going to fossil fuels in the last four years. Approximately 20 percent of that lending went to energy efficiency and low impact renewables, while about a third went to energy projects that either have significant environmental impacts, such as large hydropower, or were not identifiable as to the energy source, such as transmission and distribution projects. At the same time, less than 10 percent of its energy portfolio went to promote energy access for the poor.

Given the WBG’s poor energy lending record and its significant role in climate finance, it is clear the institution needs a new energy strategy that puts it on a new course that reflects the realities of the climate-constrained world in which we live. However, the institution has been unable to agree on a new energy strategy after a two-year revision process. Although the current draft contains a number of compromises, the WBG has reached a deadlock, adopted a cone of silence about the process, and refuses to be held accountable to its own analysis of the problem, that: “sustainable development through clean energy is still being addressed through short-term financing and regulatory frameworks that are not aligned to the immense scale of the challenge facing the globe.”

Meanwhile, the WBG appears to be disproportionately influencing and being influenced by the G20, the outputs of which do not indicate a climate-friendly course of action for the Bank’s infrastructure lending. The multilateral development banks (MDBs) produced a paper for the G20 on infrastructure that did not reflect the climate concerns that have been raised in the UNFCCC context. Then, the final report of the G20 High-Level Panel for Infrastructure Investment reinforces the call for MDBs to catalyze regional investment in the energy sector – particularly in electricity generation, transmission, and distribution. However, it fails to provide any benchmark for MDB energy investment in lowcarbon growth strategies or on scaling up climate adaptation. In fact, the recommendations make no pretensions in any way of promoting investment in energy infrastructure that would improve access to clean energy, help developing countries adapt to climate change, increase energy efficiency, or increase mitigation of greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Based on its own studies, reports and messaging, the World Bank Group has demonstrated an understanding of the impacts of climate change on development issues. However, the institution’s actions – its core energy lending, its inability to pass a forward-looking energy strategy, and its mixed involvement in climate-related initiatives – indicate that the WBG does not, in fact, take those climate change impacts nearly seriously enough. In order to change course and support developing countries in a transition to truly clean energy:

The World Bank Group must stop funding dirty energy projects, either directly or indirectly.

The World Bank Group must pass an energy strategy that promotes truly clean energy and energy access.

The World Bank Group is experiencing clear difficulties in synching its core lending and its energy strategy with climate goals, and the institution has taken steps that can easily be viewed as creating a conflict of interest. Given these difficulties and contradictions, the institution should focus on cleaning up its own act before making further forays into climate finance initiatives.