What’s the plan?

Why we can’t hide from the discussion about a managed decline of fossil fuel production.

It is clear that the end of the fossil fuel era is on the horizon. Between plummeting renewable energy costs, uncharted electric vehicle growth, government commitments to decarbonization enshrined in the Paris agreement, and a growing list of fossil fuel project cancellations in the face of massive public opposition and bad economics, the writing’s on the wall.

The question now becomes: What does the path from here to zero carbon look like? Is it ambitious enough to avoid locking in emissions that we can’t afford? Is it intentional enough to protect workers and communities that depend on the carbon-based economy that has gotten us this far? Is it equitable enough to recognize that some countries must move further, faster? And is it honest enough about the reality that a decline of fossil fuels is actually a good thing?

In short – will this be a managed decline of fossil fuel production, or an unmanaged decline? What is the plan?

Let’s take a closer look:

Is the plan ambitious: Is it fast enough to avoid dangerous climate change?

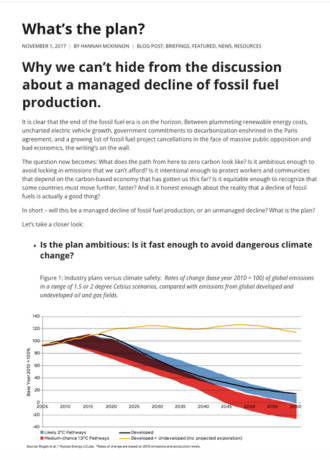

Figure 1: Industry plans versus climate safety: Rates of change (base year 2010 = 100) of global emissions in a range of 1.5 or 2 degree Celsius scenarios, compared with emissions from global developed and undeveloped oil and gas fields.

Figure 1 shows the trajectories of decarbonization necessary in for 2-degree Celsius (blue) and 1.5-degree Celsius (red) pathways. The black line is the trajectory oil and gas production would follow if we stopped exploring for and developing new fossil fuel reserves today. The orange line is what is actually on the books when you add up what industry thinks they can extract. The difference is stark. Even as renewables take off, every year more and more of that unburnable carbon is being locked into production. The picture is much the same for coal.

Without efforts to limit this production growth, a variation on one of two themes will unfold: 1. We will miss climate limits and global climate change will be catastrophic, or 2. A much more dramatic future halt and decline of production will be significantly more economically and socially disruptive.

It seems clear that managed >> unmanaged. Why wouldn’t you prepare to ensure the decline is as non-disruptive as possible, but also fast enough to avoid the worst climate impacts?

Is the plan fair: Does it prepare for a just transition that will protect workers and puts communities first?

Speed and ambition is paramount: As the International Trade Union Confederation grimly puts it, there are no jobs on a dead planet. But a key element of a managed decline is that it must come hand-in-hand with a just transition for jobs and communities that have become dependant on the production of fossil fuels.

Everyone can recognize the role fossil fuels have played in the development of the global economy, and everyone should recognize the workers and communities that have made these sectors thrive and provided the world with energy. A critical part of this transition is acknowledging that those workers and communities require and deserve support as their livelihoods change.

Trade unions and others have developed a framework for a just transition in relation to climate change, the importance of which is recognized in the preamble of the Paris Agreement. Key elements of a just transition include:

- Sound investments in low-emission and job-rich sectors and technologies;

- Social dialogue and democratic consultation of social partners – trade unions and employers – and other stakeholders, such as communities;

- Research and early assessment of the social and employment impacts of climate policies;

- Training and skills development to support the deployment of new technologies and foster industrial change;

- Social protection alongside active labor market policies; and

- Local economic diversification plans that support decent work and provide community stability in the transition.It is also important to note that the fossil fuel economy, while a massive employer, is not always a good employer. Workers and communities have oftentimes been taken advantage of in the boom and abandoned in the bust. We need a transition plan that will not just create new jobs, but that will create good new jobs.Fossil fuel extraction has impacted tens of thousands of communities around the world, and more often than not, it is marginalized populations that bear the brunt of the impacts of living and working on the frontlines of the fossil fuel economy. From chronic health problems, to irreparable local environments, to political oppression and more, these communities must finally have the agency they deserve over the future of their lives and livelihoods.

A just and managed transition will build support, not resistence, and it will do so by ensuring that those affected are meaningfully engaged from day one.

Is the plan equitable: Does it recognize that some countries need to move further, faster?

One other thing if you look closely at Figure 1 is that although the black line is much closer to the trajectory we need to be on, there is some production that will need to be retired early to stay within any reasonable climate limits. This is also clear in Figure 2 below (from The Sky’s Limit), which shows a good deal of carbon in already-producing reserves that we can’t afford to extract and burn in safer climate scenarios.

Figure 2: Emissions from Developed Fossil Fuel Reserves, Compared to Carbon Budgets

While all countries will need to undergo a managed decline of their fossil fuel sectors, the poorest nations will need significant support, including being allowed to burn their fair share of the global carbon budget to aid in the transition.

Conversely, wealthy, developed fossil fuel producers that have benefitted from fossil fuel production for decades have an obligation to prove it is possible to transition an economy off of fossil fuels (see the Lofoten Declaration for more on this). After all – if countries like Norway, Canada, or Germany can’t do it, who can?

Does the plan recognize that markets alone won’t cut it? We need leadership and action to get us where we need to go.

Clean and renewable energy solutions are imperative, but as the lock-in case above shows us, markets alone won’t do the trick even if the alternatives to fossil fuels are setting records. Fossil fuels are entrenched in our society and they have the status quo momentum that will require leadership and action to stop.

Figure 3 below, from Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s 2017 New Energy Outlook, provides another illustration of why technology is key, but won’t get us far enough, fast enough. Even the renewable energy optimists (among which we count ourselves) recognize that leaps and bounds in clean energy aren’t enough if there is a failure to limit fossil fuel production.

Figure 3: Global power sector C02 emissions

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2017 New Energy Outlook

We can celebrate the extraordinary growth of renewable energy solutions, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves about the other half of the equation. We need to sunset the fossil fuel sector, and to suggest otherwise is deceptive and dangerous. Within this, we need a just transition and a managed decline, and we need them to start now. We can both recognize the critical role fossil fuels have played in the development of society as we know it, and recognize that now we know better and it is time to move on.

The principles

Let me finish with what I see as the principles that will be critical as we move into the next decade of climate action:

Fossil fuel production decline is necessary and urgent

Managed decline >> unmanaged decline

Just transition and equity are critical

Frontlines and impacted communities are central

We must leapfrog any continued discussion about “if,” and let the science tell us “when” (start immediately) and “what” (phase out fossil fuels completely within 25 to 50 years). The important discussions we can then focus on are “how” and “who decides”.

“Managed decline” is a phrase that makes certain people nervous: Declines are “politically toxic,” and decision makers want to be able to talk about growth, not decline. But that is missing a critical point: Decline of a bad thing is good. A decline in asbestos, a decline in ozone-depleting chemicals, a decline in lead-based paint, a decline in coal. All of these are things that were useful to humanity until we learned how dangerous they were. And then their decline became the priority it needed to be, and by-in-large, rational people have been happy to see them go. It is also honest; fossil fuels will decline and a good plan is clear about its goals.

To make this work, we need first movers. We need governments that understand the urgency of climate action and have the means to act to do so, boldly. The auto industry proves instructive: After a few first movers laid down markers, the electric vehicle market is no longer niche. Recognizing that there is no other future, incumbents are tripping over themselves to come up with the plan that will keep them in the game. Governments everywhere should take note – or they, and their citizens, will find themselves wondering why they were so determined to be the last ones standing in an obsolete economy.