All Bust, No Boom

In a dramatic turn of events, it looks like all bust and no more boom for the Alberta tar sands, according to our recent analysis based on industry data. In reality, future rates of production will likely be insufficient to fill even one new pipeline.

This post is co-authored by Senior Research Analyst Lorne Stockman

In a dramatic turn of events, it looks like all bust and no more boom for the Alberta tar sands, according to our recent analysis based on industry data. With industry mouthpieces such as the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) claiming healthy growth for the sector despite a third year of anemic investment, we decided to lift the lid on what is actually going on in the tar sands patch. In reality, future rates of production will likely be insufficient to fill even one new pipeline.

As clean tech surges, the debate about the future of oil demand and oil prices is very active, so a forecast for growth that depends on a future of higher oil prices cannot be taken at face value. Most tar sands production projections rely on embedded oil price rises. We decided to set those assumptions aside to see what the actual state of play is today, and pose the question: is the end of growth in the tar sands here?

Without an assumption of robust oil price recovery, it would appear that the future of the tar sands is one without growth. Nonetheless, the Albertan and Canadian governments continue to bet on a recovery.

The sector has seen a dramatic exodus of international oil companies (IOCs) over the last year, including Statoil, Shell, ConocoPhillips, and Marathon, with BP and Chevron also reported to be considering pulling out. Our research suggests that the IOC retreat is symptomatic of building market headwinds facing the tar sands.

A combination of the drop in global oil prices, successful campaigns to delay and stop major infrastructure, and the looming implications of climate action have toppled the narrative that continued growth is inevitable in the high-cost, high-carbon tar sands oil sector.

Instead, as we show below, there is currently no commitment to project construction beyond 2020.

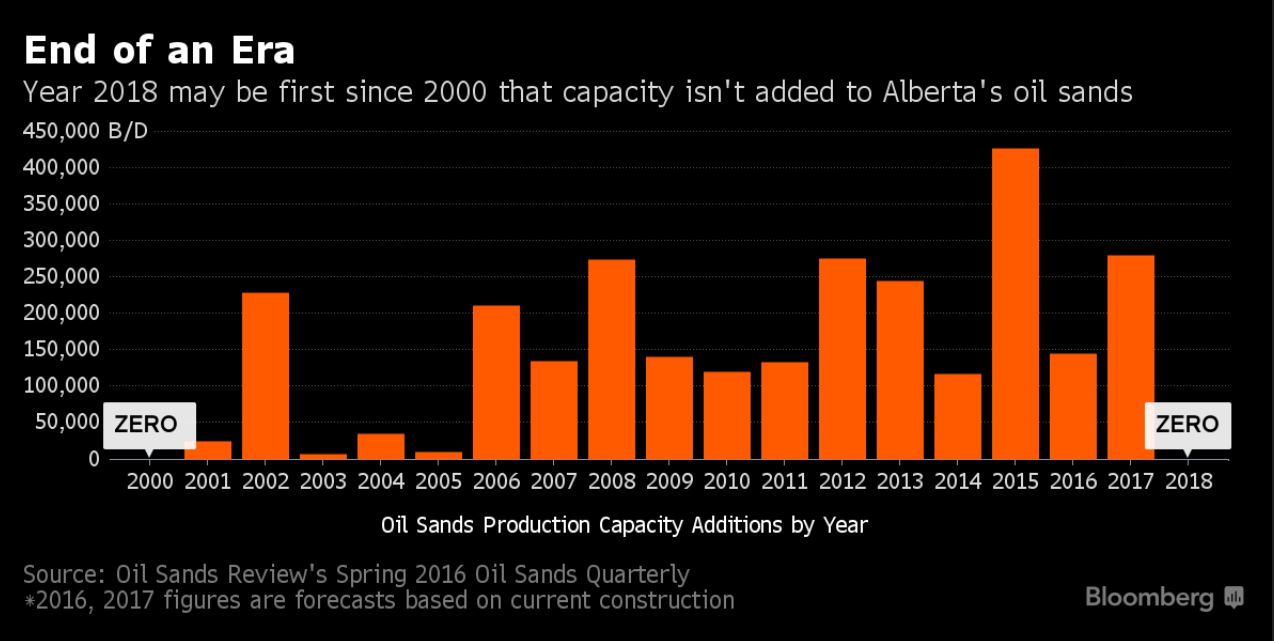

Figure 1 shows the steep decline in project approvals since 2013. Note that in 2017, no new capacity has been approved to date.

Figure 1: Tar sands capacity additions by approval year

Figure 2 (below) shows the annual capital expenditure (capex) spent on developing new tar sands production capacity since 2000. Projected capex beyond 2016 only includes investment in projects that have already been approved. This capex ends in 2019 as currently under construction projects begin production. For that to change, new projects will have to be sanctioned by oil companies.

Figure 2: Tar sands capex in new project construction/development

This is a dramatic change of events in a sector that just a few years ago was anticipating major expansion and sustained growth. Instead, the sector is facing the end of any significant capex in new growth, and the challenge of trying to squeeze a profit out of projects that were sanctioned in a $100-per-barrel world in one that is instead moving towards decarbonization.

Figure 3: Breakeven price requirements for tar sands projects (2030 production point)

Figure 3 (above) indicates that no significant growth in the sector can be expected unless prices reach $70-75 USD per barrel. The most substantial growth would only come at $75-80. However, companies will only develop projects if they expect prices to be sustained at that level for the 20 to 25 years required for the projects to break even. Small developments may occur at prices below $70, but well below previous growth rates in the tar sands, and not at rates sufficient to fill even one new pipeline.

This new reality throws yet another massive hurdle in the path of the Trump-supported Keystone XL pipeline: producers don’t want it. With nothing on the horizon in terms of new growth, no matter what the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers says, pipelines are no longer a hot commodity. CAPP is pulling out all of the stops (magic tricks with numbers and a full-fledged PR push) to keep pipelines in the limelight, but when market forces turn against you, no amount of talking up your book can save you.

So what does this mean for the sector, decision makers, and campaigners?

The tar sands sector: With IOC flight from the tar sands, Canadian companies have mostly been left holding the reins. In broad strokes, their choices could include the following:

Forecast failure: Ignore forecasts that are based on successful climate action and assume that oil will rebound dramatically to sustained high prices over the long term.

Ignore reality: Assume that even if climate action does take hold and global demand falls, that the tar sands will somehow be one of the last sources of oil standing as the world decarbonizes. This assumption appears to rest on future cost-cutting and emissions reductions fantasies (you generally cannot have both), and in all likelihood tar sands production will be the first casualty of serious climate action due to its high carbon content. Canada has a significant historic responsibility for emissions and the relative wealth to support a transition; the sector doesn’t align with any reasonable climate-safe future.

Diversify: Phase-out of tar sands production and begin a shift to an alternative energy business model.

Financial managed decline: Manage an accelerated decline of the business and return capital to investors.

Oil Change international has outlined the risks of the first two approaches, and is beginning to explore what a managed decline for the sector could entail. The first two come at the obvious peril of the climate, budgets, and workers and communities.

Decision makers: Provincial and federal decision makers appear attached to playing politics with the issue. With support for new infrastructure, budgets that take on significant near-term deficits, and a general commitment to doing whatever it takes to help the sector get back on its feet, provincial politicians in particular are playing a risky game. In this regard they are making the same risky assumptions industry must make with the first two choices above.

This analysis should be a reality check. Forward-thinking governments that care about workers and communities should be broaching the tougher conversations about how to drive and support a just transition for workers and communities and regulate a managed decline of the sector towards decarbonization.

Campaigners: This data is not a justification for thinking our work here is done. The fossil fuel industry specializes in making itself seem indispensable, and they will be digging in their heels over the coming months and years to do as much climate damage as possible while they still can. The evidence can be seen in the increasing clamor to ditch regulations and support new infrastructure. We know that markets alone – even with the most ambitious forecasts of clean technology – will not be enough to avert dangerous climate change: government intervention is required.

We also have a critical role to play in defining, demanding, and ensuring a just transition. Frontline communities, vulnerable people, and workers are going to be caught in the crossfire if this inevitable decline isn’t managed.

Oil Change International feels strongly that it is countries like Canada – wealthy, stable, fossil fuel exporters – that must show leadership in phasing out fossil fuel production in addition to reducing emissions. Reducing emissions at home while simultaneously exporting large amounts of oil to be burned elsewhere undermines global efforts to tackle climate change. In Canada, you could compare it to exporting asbestos even after its use has been banned at home.

The tar sands sector is on a downward trajectory, but it needs to be happening faster, and it needs to be managed to avert impacts on people and communities who have come to depend on it.

Stay tuned for more from us as we explore what a managed decline of major fossil fuel exporting countries could look like.