COP29 Explainer: Why we can’t rely on the private sector to finance the energy transition

Our new analysis shows many governments and finance models overstate the role the private sector can play in financing a just energy transition. This is coming to a head with the deadline for a new climate finance goal (NCQG) at COP29, where rich countries are using this outdated myth to try to get off the hook to pay their fair share for climate action.

Executive Summary

The deadline for a new climate finance goal (NCQG) at COP29 means the rich countries most responsible for the climate crisis are being called on to pay their fair share for a fossil fuel phaseout and other global climate action. To avoid paying what they owe, Global North governments are arguing that the private sector can cover most of the bill for a just energy transition. In our new analysis, we show this proposal is a set-up for failure. This ‘private sector first’ approach has been tried and tested and is not generating the scale, distribution, or quality of funding needed:

- There is an estimated global energy transition finance gap of $5 trillion per year between now and 2030, with the largest shortfalls in the Global South and key sectors like grids and storage, public transit, housing retrofits, and support packages for fossil fuel workers and communities.

- Increases in global clean energy investment in the last decade have been overwhelmingly limited to OECD countries and China, with the low- and lower-middle income countries that make up 42% of the population receiving just 7% of investment in 2022.

- To fill these finance gaps, the primary solution put forward by Global North countries in the NCQG negotiations is to rely on a small amount of subsidized (“concessional”) public finance to attract a much larger amount of private finance. The major studies and proposals they point to typically expect each dollar of concessional public finance to attract $5 to $7 in private finance for the energy transition in the Global South.

- Our analysis shows that in practice every $1 of concessional public finance leverages only 85 cents in private finance for energy transition projects. In low-income countries this drops to 69 cents. Thus, an NCQG premised on lofty private finance ‘mobilization’ goals is likely to lead to continued massive shortfalls in funding for a just energy transition.

- Beyond underdelivering on urgently needed funds, a narrow focus on attracting private finance risks deepening social and economic injustice. Where it is already in use, this approach is often adding to the record-breaking debt crisis in the Global South, driving austerity and privatization policies, adding barriers to building locally-owned clean energy sectors, and driving profits disproportionately to banks and corporations in rich countries.

Public funding on fair terms is needed to unlock a just energy transition. An NCQG of at least $1 trillion per year in grants from Global North countries is needed to avoid climate breakdown and save lives. At least $300 billion per year of this is needed for a just energy transition and other mitigation needs.

As previous Oil Change International (OCI) analysis shows, there is no shortage of public money available to do this. Global North countries can mobilize well over $5 trillion annually for the NCQG and climate action at home by ending fossil fuel handouts, taxing the rich, and changing unfair financial rules.

A strong NCQG is key for a just energy transition

Last year at COP28, governments committed to transition away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly, and equitable manner. Agreeing to a strong new climate finance target (NCQG), due at COP29, is the next key step to deliver on this commitment. To unlock a just energy transition, the new target must commit at least $1 trillion every year in grants, not loans, for adaptation, mitigation, and loss and damage. To date, Global North countries, which bear the largest historical responsibility for climate change and the greatest economic capacity to address it, have failed to take the lead to reduce emissions at home and pay their fair share.

This track record has continued in the lead-up to COP29. Global South countries are unanimously calling for $1 trillion or more in majority grants-based finance for the NCQG. Yet, in three years of negotiations leading up to COP29, not a single Global North government has come to the table with a potential target for public finance in the NCQG beyond the existing $100 billion per year they committed to in 2009. Instead, they have emphasized “the importance of the private sector, blended finance, domestic resource mobilization and innovative sources.” In particular, they have been advocating for the main target in the NCQG to be a wider ‘investment layer’ made up primarily of private finance on commercial terms. This approach would allow them to continue to shirk their own responsibilities to pay up for climate action with public money.

In this analysis, we look at the track record of this ‘private-sector first’ approach to finance for the just energy transition. Energy transition investment is the area of climate finance in which Global North governments are emphasizing this approach the most, with some proposals even suggesting public grants or highly concessional finance will not be needed at all. Compared to loss and damage, adaptation, and other areas of mitigation, it is true that more projects within the energy transition are potentially profit-generating. However, the extent to which this is the case is being overblown. Far from being pragmatic, this approach is failing to deliver on both the quantity and quality of finance where it is needed most.

Current trends show a massive shortfall in funding for energy transition, especially in the most-impacted regions and many key sectors.

While the last four years have seen an encouraging surge in investment in the energy transition, we are still far off track from what is needed to keep warming within safe limits. Global investment in the energy transition totaled an estimated $2 trillion in 2023.

In contrast, the average estimate across major studies of the global investment needed each year from 2023 to 2030 is more than three times larger at $6.6 trillion.1 But these top-down global finance models have significant limitations and biases – in particular, almost all of them exclude the costs of building out public transportation and rail, relying solely on switching to electric vehicles. None of them include the measures needed for a fair fossil fuel phaseout (including social protection measures and reskilling for impacted workers and communities, economic diversification, site clean-up, and collective participation in planning). After adding in the best available global estimates of the costs associated with rail and public transit expansion and a fair fossil fuel phaseout, we get a total global energy transition cost estimate of $7 trillion per year. This leaves an estimated global energy transition finance gap of $5 trillion per year between now and 2030.

This shortfall in finance is not distributed evenly. Most troubling is that the recent increase in energy transition finance has been almost entirely contained to high-income OECD countries and China, with totals for the rest of the world nearly stagnant since 2015. Low- and lower-middle income countries received just 7% of global energy transition investment (public and private) in 2022 while making up 42% of the global population. This was 17 times less per capita than in high-income countries.

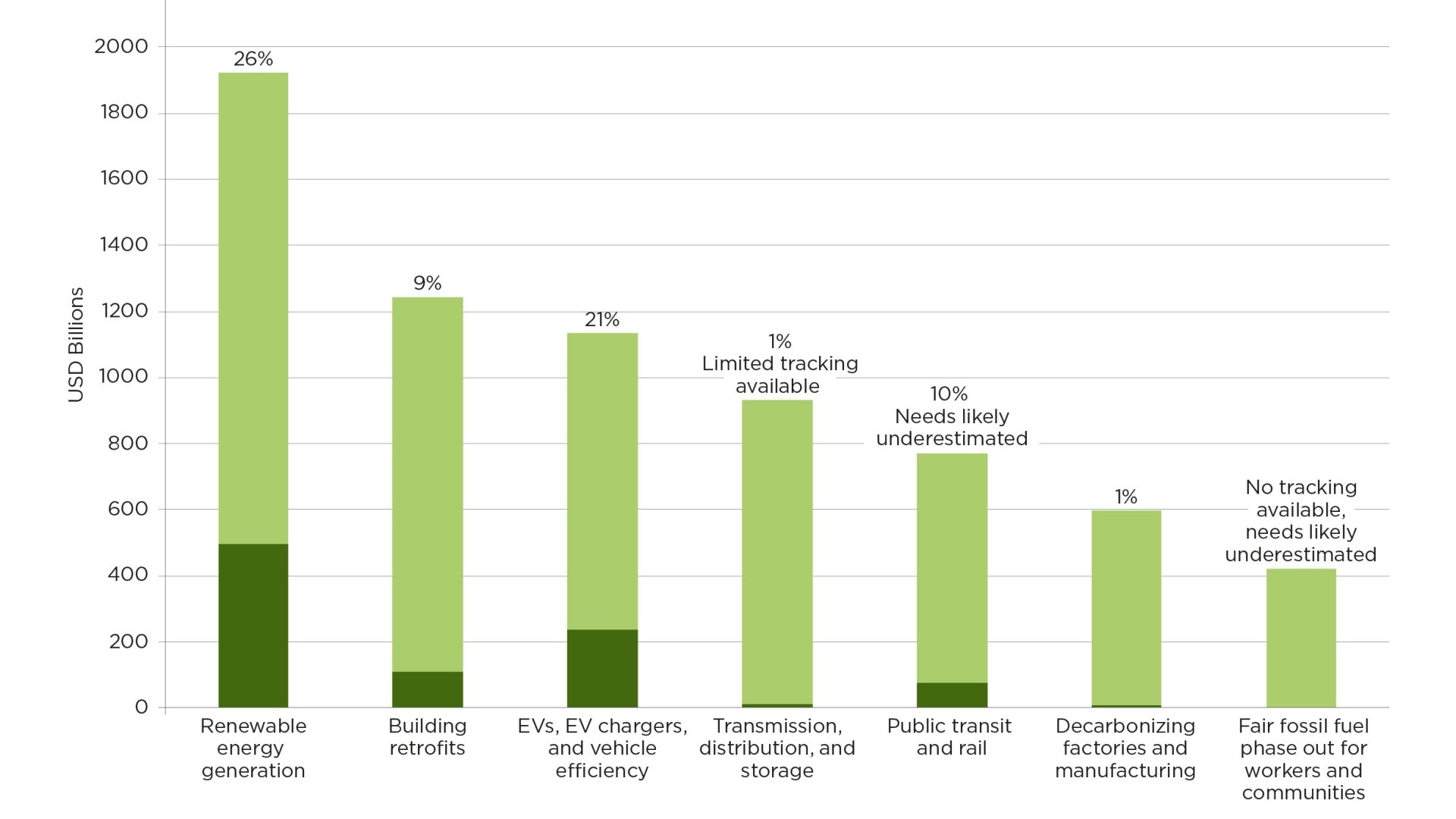

The shortfall in finance is also largest in many of the key sectors essential to enabling the scale-up of renewable energy and to ensuring the transition off fossil fuels does not exacerbate existing inequalities. Globally, measures for a fair fossil fuel phaseout, energy efficiency in buildings, rail and urban transport, renewable-ready grids, storage, and other solutions to integrate renewables into grids are among the most behind sectors for investment. Tracked finance in these sectors is 10% or less compared to the average annual need indicated by 1.5 degrees Celsius aligned scenarios (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Financing for the energy transition is most off track for a fair fossil fuel phaseout, 100% renewable-ready grids, energy efficiency, and public transit. Estimated annual finance needs for energy transition by subsector compared to annual tracked finance.

Source: Oil Change International analysis of data from Climate Policy Initiative, Civil Society Equity Review, and International Energy Agency.

The ‘private sector first’ approach already has a track record of failure

In the context of the NCQG negotiations, the primary solution posed by Global North governments to fill these energy transition finance gaps has been ‘blended finance.’ This means using small amounts of subsidized (“concessional”) public finance to try to attract a much larger amount of private finance.

Such proposals fall within a longer history of a ‘private sector first’ approach to financing global development and energy needs that has been mainstreamed by Global North governments. This has been called de-risking, Billions to Trillions, the Wall Street Consensus, the Cascade Approach, and Maximizing Finance for Development among other labels.

This private-sector first approach is based on the core assumption that public money is both scarce and fixed. Proponents recognize that on its own the private sector is not investing enough to make an energy transition happen (let alone a ‘just’ one). However, rather than working to mobilize the public finance needed to directly deliver many of the key ingredients for a just energy transition, they limit the role of governments and public finance institutions to setting small financial incentives and policy changes that aim to make the investment less risky or more profitable for private investors.

Over the last decade plus, this approach has already amassed a track record of failing to mobilize the scale of funding promised by its proponents and needed by Global South countries. Examples include:

Multilateral Development Banks’ ‘From Billions to Trillions’ Strategy (2015), Hamburg Declaration (2017), and Maximizing Finance for Development (2017).

- Goals: Before the Evolution Roadmap and Triple Agenda for “bigger and better” multilateral development banks (MDBs) that are currently in the spotlight, the G20 and the MDBs set a series of similar strategies and targets for the banks to raise trillions to meet the Sustainable Development Goals or other climate and development aims by making leveraging private finance the main goal of both their public development finance (financial de-risking) and their technical advice and policy guidance (policy de-risking).

- Result: A UN commissioned study released in 2021 found that for every dollar committed to climate finance by development banks, less than 25 cents in additional private finance was mobilized. Similarly, a 2019 study from Overseas Development Institute found that MDBs and bilateral development finance institutions (DFIs) mobilize just 75 cents of private investment in low- and middle-income countries for every dollar of concessional capital loaned for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This fell to 37 cents in low-income countries.

Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs): In 2021 and 2022 four JETP funding packages were announced as partnerships between G7 countries and South Africa, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Senegal.

- Goal: The goal of JETPs is to use concessional finance to mobilize private finance in support of a just transition away from fossil fuels. Each country plan assumes crowd-in rates of between $5 to $7 private dollars for every public dollar.

- Result: So far, South African and Indonesian JETPs have raised one-tenth of the private finance aimed for. To date, none of the JETPs have generated concrete plans for how they will contribute to the ‘just’ element.

Despite the evidence that private-sector first approaches are already under-delivering in mobilizing promised levels of finance in other contexts, Global North-driven proposals for the NCQG are doubling down on this approach again as the way to cover the bill they owe for the energy transition.

In this case, a key assumption is that ‘blended finance’ for the energy transition may work in a way it has not for the SDGs – and cannot for adaptation and loss and damage – because more projects within the energy transition are potentially profit-generating and attractive to private investors. The major studies and proposals Global North governments point to typically assume every $1 of concessional public finance will attract, or ‘crowd in,’ $5 to $7 in private finance for the energy transition in the Global South. But, to date, there has been no comprehensive analysis of whether this assumption is borne out by the evidence. In the next section, we dig into the data.

Definitions

At COP29, governments are negotiating not only the amount that Global North governments are committing to pay under a new climate finance target, but also what types and quality of finance will count towards it. The key types of finance relevant to the NCQG are:

- Grants — Funds that are not repaid and thus debt-free.

- Concessional Finance — Loans or other financing instruments provided at terms more favorable than market conditions. This includes lower interest rates and longer repayment periods.

- Commercial or market-rate finance — Loans where the interest rate is set by the current market conditions, including inflation, cost of capital, and risk. Typically with more fixed repayment terms and conditions.

- Blended finance — financing that: “combines concessional public finance with non-concessional private finance and expertise from the public and private sector.”

The evidence on the energy transition: Blended finance is delivering ‘Millions to Millions’ not ‘Billions to Trillions’

Blended finance is being held up as a solution to unlock large sums of private money to fund the energy transition. However, there is not yet a comprehensive analysis of how blended finance is performing when it comes to the types of investments required to phase out fossil fuels and build a renewable economy in their place. To start to fill this gap, we built a transaction-level database of renewable energy and other energy transition-related blended finance projects between 2014 and 2023 based on publicly available information and supplemented with project finance information from the IJGlobal and Convergence databases.

Our database includes 184 projects related to the energy transition that were part of blended finance initiatives. These projects have a combined value of $20 billion. All of the transactions in our database provided concessional public loans in order to mobilize other sources of both public and private non-concessional finance. Our methodology can be found here.

Our analysis shows that between 2019 and 2023:

- Every dollar of concessional public finance brought in just 85 cents in private finance for energy transition projects. This is significantly lower than the $5 to $7 dollars that the International Energy Agency (IEA) and JETPs assume every dollar in public finance will be able to leverage.

- Blended finance performed worse in low-income countries, where just 69 cents of private investment was mobilized for every dollar of concessional public finance. These countries also received a small share of blended finance investment overall – just 10% of all finance tracked in our database. This is despite blended finance being named as a tool to “catalyze renewable energy investments in low-income countries.”

- Concessional public finance attracted far more other public finance than private finance. Each dollar of concessional public finance attracted $2.67 of public finance on commercial terms from development finance institutions and other government-owned entities. Many development finance institutions emphasize ‘private capital mobilization’ ratios as a key metric, defining this as the rate of private investment leveraged by total public finance. If we state our findings in these terms, for every dollar of public finance (concessional and commercial), just 32 cents of additional private finance was brought in.

Figure 2: Blended finance for energy transition projects by country category and finance type, 2019-2023, USD millions

Source: OCI analysis of data from Convergence© and IJGlobal

Relying on private finance brings us further from a just transition

A narrow focus on using public money to attract private finance often comes with serious human costs, on top of severely underdelivering on quantities of funding.

Prioritizing profitability above other criteria is resulting in public funds going to places and projects most likely to deliver profits to the private sector, rather than to where they are most critically needed. Catering to profit motives also provides incentives to skirt human rights, labour rights, and environmental safeguards.

Where it is already in use, this approach is often adding to the record-breaking debt crisis in the Global South, driving austerity and privatization policies, adding barriers to building locally-owned clean energy sectors, and driving profits and other economic benefits disproportionately to banks and corporations in rich countries.

A serious consequence of a private finance first approach is that when international public finance does flow to low- and lower-middle-income countries, it is overwhelmingly flowing as loans (83%) at a time when 93% of the countries most vulnerable to the climate crisis are in or at significant risk of debt distress. This is exacerbating widespread cost-of-living and energy poverty crises. Rather than actually ‘de-risking’ investments, in reality, the risks are just being transferred from the private sector to the public through debt creation. This risks further austerity and cuts to essential public services, which in turn further widen inequality.

Privatizing the energy transition also undermines opportunities for public participation, and a democratic, community-led process to determine how the energy transition will unfold at the local level.

This also means that the public loses out, subsidizing private profits and losing potential revenue for public goods. For profitable mitigation projects, this represents a missed opportunity to adopt energy ownership models that build up local control and expertise along the value chain and can generate public and community wealth. Such wealth can in turn be reinvested to deliver other public goods and services – including the less profitable parts of a just energy transition. As governments plan to triple renewable energy and double energy efficiency by 2030, much more discussion must be had on private versus public ownership and control of our future energy system.

Global North country proposals for the new climate finance goal that rely on private finance set us up for failure

In summary, our analysis underscores that proposals for the NCQG that rely heavily on mobilizing private finance, instead of Global North governments paying their fair share with public money, are both unrealistic and unjust.

Based on needs assessments, Global South countries and civil society experts are calling for a minimum of $1 trillion per year in grants-based finance for the NCQG overall, with a subgoal of at least $300 billion for the energy transition and other mitigation needs. By contrast, private finance-centered proposals being used by Global North countries, including those from the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG), the IEA, and the IMF, suggest setting a provision goal for mitigation that is 5 to 24 times smaller in grant-equivalent terms than the $300 billion per year that is needed. And these proposals are 34 to 139 times smaller than precautionary proposals based fully in historic equity – with these estimates ranging from between $5 trillion to $6.9 trillion annually.

Many of these private sector-centered proposals also rely on Global South domestic public contributions that ignore historic equity and the limitations that our current global financial architecture places on domestic resource mobilization. As one outcome of this architecture, debt repayments absorb an average of 42% of budget revenue in the Global South. The recent protests in Kenya against a proposed IMF-imposed Finance bill – which would have made basic necessities unaffordable while burdening ordinary Kenyans with more taxes to pay off rich country lenders – is just one example of the consequences of the limited fiscal space many Global South countries are facing in the midst of a crushing debt crisis. Yet, proposals continue to rely on Global South countries to raise significant new funds with little mention of debt cancellation, or tax reform including ending illicit financial flows alongside other changes to global financial architecture reform. For example, the IHLEG proposal requires nearly triple the IMF’s estimate of what total additional Global South tax revenues are achievable in the next 2 to 3 years.

At COP29, the Global North countries most responsible for the climate crisis are being called on to pay their fair share for a fossil fuel phaseout and other global climate action. Committing to a public, grant-based NCQG is urgently needed to enable an energy transition at the pace and scale required and to ensure this transition is fair and just – avoiding making Global South countries pay for a crisis they did not cause and further exacerbating debt distress. There is enough public money to ensure a full, fast, fair, and funded fossil fuel phaseout and build a 100% renewable economy in its place. Now is the time for Global North countries to deliver it.

- To reach this total, we have included the average costs for energy production as well as the changes needed to transition to net-zero energy end-use in the building, transportation, and industrial sectors compiled by Strinati et al., Top-down Climate Finance Needs.