Dirty deal lubricates the path to oil exports

Last night Congressional leaders succumbed to the intensive oil industry campaign to lift the ban on exporting crude. The industry wants to export in order to get higher prices. Not only would this keep full the coffers of the opponents of climate action, it would incentivize increased extraction.

Our Executive Director Steve Kretzmann, had this to say:

“Congress’ response to an historic climate deal in Paris? Incentivize further oil production. It’s hard to imagine a clearer example of how far politics still has to go on climate in order to catch up with the science.”

So dirty money in our political system looks set to win the day (although people power is ensuring that it won’t win the year).

Disappointingly, it seems some relatively climate-progressive Representatives and Senators also supported lifting the ban, in return for extending some tax credits on renewable energy. It was a tawdry deal.

Both renewables schemes – the Production Tax Credits (PTC) for wind energy and Investment Tax Credits (ITC) for solar – are an important part of the framework for growing US production of twenty-first century clean energy. But the actual extensions proposed are short, small and of limited climate impact.

In return for lifting the oil export ban in perpetuity, the two renewable tax credits were extended for just five years, and both phased down to zero over that period (except for businesses developing solar, where ITC is phased down to 10%).

Hoping to inform decisions about the expiring PTC, in September the National Renewable Energy Laboratory published a study on the impact of extending the credit. It found that maintaining the PTC at its current level could have a significant impact on growth of the sector. In contrast, a phased-down five-year extension – which the Congress deal proposes – would have negligible impact compared to ending the PTC altogether. See if you can spot the difference between the charts below.

Chart: Projected cumulative wind capacity, with PTC expiration and with PTC phasedown to 2020, in low (solid line) and high (dotted line) deployment scenarios.

It appears the politicians may not have read the advice they were given.

(To our knowledge there’s no similar official projection on extending the ITC for solar, but an analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance for SEIA recommended maintaining it for five years at its current level (not phasing it down), in order to sustain industry growth).

Much more emphasis was granted in debate around the deal to an Energy Information Administration (EIA) study, also from September, on the impacts of lifting the crude export ban.

In its reference case, the EIA concluded that lifting the ban would not increase production. The underlying reason was that lower oil prices have stopped the growth of US tight oil production, so there’s no longer a surplus relative to refining capacity, and so no longer a price differential. (It is worth noting, given how much that projection appears to be relied on, that the EIA’s reference case scenarios have not always tracked well with real world trends – as demonstrated here and here and here).

In other scenarios, the EIA estimates that lifting the ban could increase production by 380-470 thousands barrels per day (kbd) by 2025. The increase in production in EIA’s various scenarios is shown in the chart below.

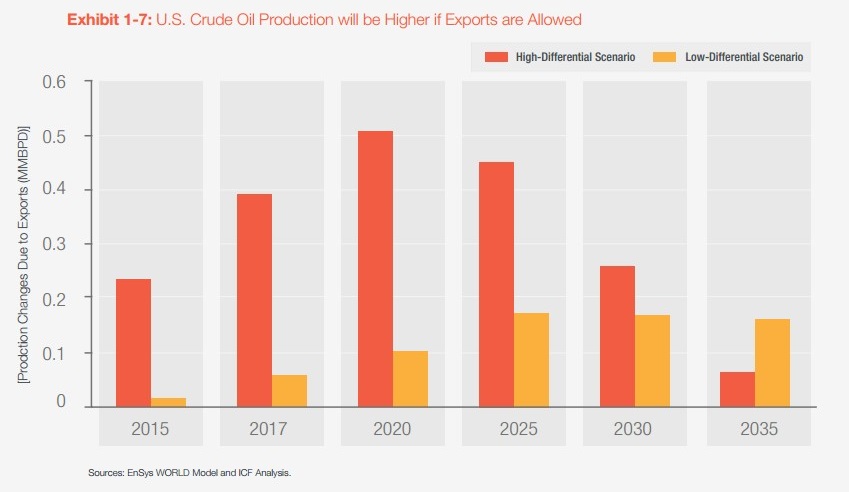

The oil industry itself does not consider the possibility that lifting the ban could have a zero impact on production. A recent report by the American Petroleum Institute suggests the impact could be between 180 kbd and 470 kbd in 2025 (below).

It is true that in the short term, lifting the ban would have less direct impact than if oil prices were still high. But the industry is playing a long game, and as we noted lifting the ban is forever, not for a tapering five years. Even if the short-term impact were zero (as in EIA’s reference case), it would become material once prices rise (remember: oil prices go up and down). In any case, the climate impact of lifting the ban would increase when prices are higher.

And this is not insignificant. Assuming life-cycle emissions of 470 kg CO2e / bbl (a conservative estimate, assuming low levels of gas flaring), an increase of 470 kbd would translate to 81 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year: the equivalent of 21 coal plants.

Professional sceptics continue to doubt the importance to climate change of fossil fuel supply. In reality, the climate problem is caused by the quantity of fossil fuels, which can be addressed at either end of the supply chain, as the same amount is consumed as is extracted. And given the fracking boom, the US is once again becoming important as a fossil fuel producer as well as consumer.

With this deal, not only have Congressional leaders given a boon to the oil industry in exchange for a negligible nod to renewables, they have traded the climate for oil industry profits.

To get truly serious about addressing climate change, Washington must end the billions in subsidies going to the industry and move to keep fossil fuels in the ground by banning drilling offshore and ending the fossil fuel leasing program on public lands.