EIA AEO 2016 Early Release: a quick overview

We give a quick overview of the EIA’s early release of the AEO 2016, and recommend you take their advice. This is not a forecast.

Energy outlook-watchers like ourselves got a mild surprise this morning when the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) produced an early release summary of its flagship annual publication, the Annual Energy Outlook (AEO). The full version is expected in July.

This release, which provides projections for US energy out to 2040, follows closely on the heels of last week’s publication of the International Energy Outlook 2016 (which we discussed here). As today’s early release features only the two main cases from the full report, it would be premature for us to criticize the lack of a “climate safe” case that could guide US policy makers in achieving the nation’s climate commitments. But let’s just say that we’re not holding our breath for this.

Here are some key points that stood out to us about today’s new data and how EIA presented it.

First, the release announcement stood out because the framing appeared to be in direct response to criticisms voiced last week during the IEO 2016 launch – not least by Oil Change International – that the projections made in these publications should not be taken to be predictions or forecasts, as they so often are. The EIA’s response could not have been clearer, as they announced today’s release on the EIA blog with the headline: “EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook is a projection, not a prediction“.

But what about the data?

A lot has changed since April 2015 when the last AEO was released. The EIA’s “Reference Case”, which they carefully point out is a “projection” based on existing laws and policies and technology, now includes projections based on Clean Power Plan (CPP) implementation, as well as the extension of tax credits for wind and solar energy that were passed in December 2015’s budget bill. So the model now incorporates one of the Obama Administration’s flagship climate policies as well as the relative stability on renewable energy policy that the sector had been missing for some time.

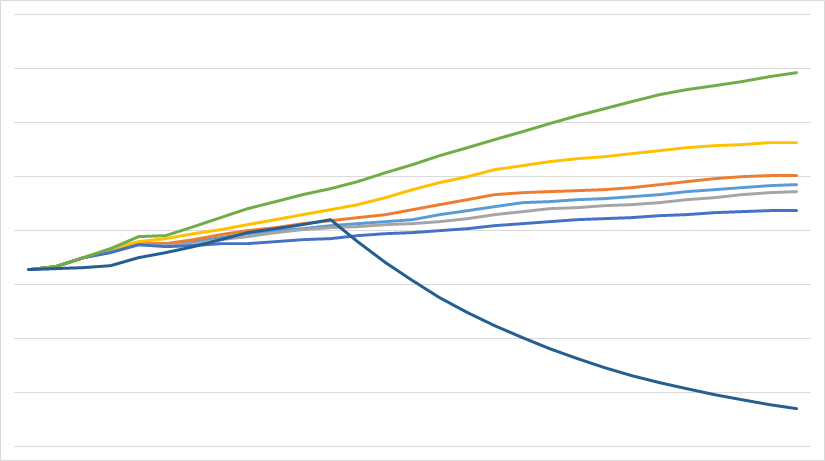

Very briefly, this is what the EIA model projects for US emissions, fossil fuels, and renewable energy under the Reference Case:

Emissions: US energy-related CO2 emissions in 2040 are just over 5 billion metric tons, which marks only an 8% decrease from 2014 numbers. Needless to say, this is not in line with US commitments to cut emissions 83% from 2005 levels by 2050.

Natural Gas: Natural gas is the fossil fuel that just keeps giving, to hear EIA tell it. Not only is gas production set to rise over coming years, but each year the EIA keeps raising its projection. This year’s AEO has gas production rising 50% from 2014 levels by 2040; last year’s report had it pegged at 34%.

Coal: Coal in the power sector drops 40% by 2040, but that means there would still be nearly 500 million short tons of our most polluting fossil fuel going up in smoke. That’s an improvement on the rise to over 900 million tons projected in the AEO 2015, but it’s a long way from decarbonization.

Oil: Total petroleum use rises around 4% between 2014 and 2040, according to the 2016 AEO. While oil production rises 27% in the same period, consumption is projected at over 60% more than production in 2040. What was all that talk about energy independence?

Renewable Energy: Renewable energy grows 257%, and that doesn’t take non-grid-connected systems into account. But considering solar energy alone has grown 173% since 2011, this seems very under-ambitious for the sector as whole over the next 24 years.

We will wait for the full report before going into the details of this year’s AEO and what it needs to do to better inform policy makers seeking to steer the US away from the climate catastrophe that these projections align with.

In the meantime, heed the EIA’s advice. The AEO is not a forecast or a prediction. These are projections that can inform policy making and help us understand the consequences of energy policy decisions and investments.

As such, we need to be clear that much greater policy intervention is needed for the US to play its role in maintaining a safe climate. Making sure the projections in the AEO 2016 do not come to pass will be central to that task.