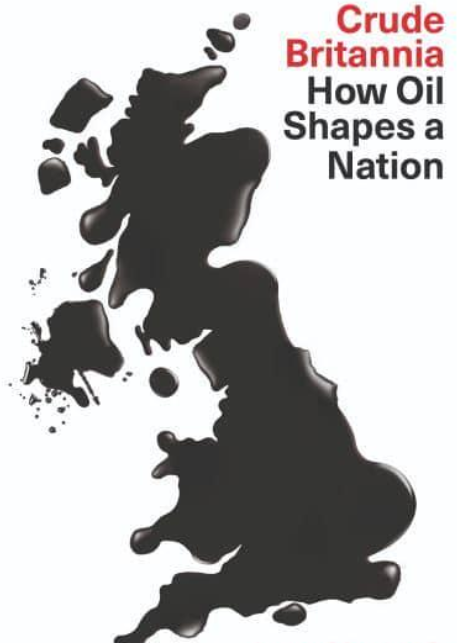

Crude Britannia: Understanding how oil shapes a nation

There is a great and timely book that has been published entitled Crude Britannia, which looks at how oil has shaped society and the political landscape of the United Kingdom.

As climate campaigners look to build on three seismic victories against Big Oil in the last couple of weeks, including the landmark Dutch legal victory against Shell, many hope these victories will be the tipping point in the decades-long struggle to force oil companies to adequately respond to our climate emergency.

As climate campaigners look to build on three seismic victories against Big Oil in the last couple of weeks, including the landmark Dutch legal victory against Shell, many hope these victories will be the tipping point in the decades-long struggle to force oil companies to adequately respond to our climate emergency.

Even now we face an uphill struggle, though. And in further taking the fight to Big Oil, we need to understand how deeply embedded into society fossil fuel companies are. We cannot break free of the shackles if we do not understand the mindset and magnitude of the fossil fuel giants.

To this end, there is a great and timely book that has been published entitled Crude Britannia, which looks at how oil has shaped society and the political landscape of the United Kingdom.

Written evocatively and beautifully by long-term activist, James Marriott from PlatformLondon and Terry Macalister, ex-Guardian newspaper journalist of thirty-five years, it is part travelogue, part history book, and part detective novel. Weaved throughout the book are the characters whose lives have been dominated by oil.

The pair speak to the oil executives such as Ben van Beurden from Shell, scientists, and ordinary rank and file oil men, who have given the industry their lives. They interview a new breed of female renewable energy bosses, climate campaigners such as Extinction Rebellion co-founder, Gail Bradbrook and songwriters.

As with most great books, this is not written on a whim or a whisper. This is five years of meticulous research and insight based on decades of hard-learnt experience. If you want to understand how oil engulfs our lives and is embedded into the core of our society, then you need to read this book.

Sometimes the power of the oil industry is so ubiquitous and universal that it goes unseen. But this book shines a light over the shadow of Big Oil. What do we even mean by the oil industry? Platform’s pioneering work years ago highlighted how we need to understand the whole carbon web, from the companies themselves to the financiers behind them or the spinoff petrochemical companies, to the politicians in their pockets or PR companies spouting their propaganda.

But to really understand power, we need to piece together the industry’s economic and political influence, and how this plays out across the land and sea. The authors assert that “the United Kingdom is a land formed by oil. London, shaped by petroleum. Four estuary regions – the Thames, Severn, Mersey and the Forth and Dee – moulded by the industry for almost a century. And most distinct, the North Sea, turned into an offshore colony run largely by a handful of corporations”.

The authors take us on a journey of key oil areas such as the Thames Estuary, Merseyside, North East Scotland, and South Wales which have been shaped by the oil industry for decades. The book unravels Shell’s Nazi-loving dark past: “There is an embarrassment about Shell’s role in the Nazi state.”

Foreign policy has been heavily influenced by oil needs. British colonies such as Nigeria and Trinidad, and other states such as Iran and Libya were prized largely because of their oil and gas reserves. There are also decades of corporate shame for Shell over its collusion in human rights abuses in the Niger Delta — and authors Marriott and Macalister interview Lazarus Tamana, now head of Mosop, the Movement for the Survival of Ogoni People, once headed by the famed Nigerian writer, Ken Saro-Wiwa.

The book charts how oil made its way from the troubled waters of the Niger Delta to the Welsh port of Milford Haven. “Wales was transformed through the building of infrastructure that could ingest a massively increased crude load and then process it into petrol, plastics, and pesticides.”

The book also addresses climate change. As Marriott and Macalister note: “most of us are concerned about oil due to climate change. Both of us are deeply concerned by the human-driven changing of the Earth’s climate. It will dominate the rest of our lives, and those of friends and family. The greatest source of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels. What is the role of the oil companies, whose profitability is built on this process, in shaping the UK’s response to climate chaos?“

All around us the same oil companies eagerly promote their desire to decarbonize themselves and the UK. Are they doing this in response to civil society pressure about the climate? Or do they see themselves under a greater threat from the rise of Big Data corporations? A threat so powerfully illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic “that shifted the country from commuting to computers, from cars to Zoom.”

There is also a warning about the shifting patterns of who is the power house behind our ongoing addiction to oil. “As things return to ‘normal’ after the pandemic there are still as many trucks on the road and almost as many planes in the sky, there is still as much plastic in the kitchen and pesticides on the fields,” they warn.

“Yet the control of this bloodstream of our society is now in the hands of a very few wealthy men entirely hidden from public view, beyond the reach of politicians, trades unions or civil society groups.”

These secretive oil men are not so vulnerable to public pressure or shareholders’ revolts, as we have seen with Exxon and Chevron recently. “Those that own the private equity companies want from Britain the highest return on their capital and the lowest taxes possible, with the least stringent regulations. The last thing they desire is for limits to be put on the sale of fuel as a way to tackling climate change.”

“Whereas the heads of BP, Shell and other corporations may profess a commitment to decarbonize to appease an alarmed public, the private equity men are hidden from view and pressure,” write Marriott and Macalister.

We also need to understand how far the tentacles of the modern carbon web go. “So when climate protesters call for divestment from BP to Shell we should understand that the next phase of any campaign needs to include less well-known names such as Ineos, Chrysaor, or Neptune, plus Chinese and Middle East groups,” write the duo in an article for the release of the book.

Once you have read Crude Britannia, you understand how truly oil is embedded in our lives. We have come so far but there is still so much more to do in the climate fight. In the meantime, there is hope.

“We set out on our journey,” say Marriott and Macalister, “to highlight how oil and its industry had shaped Britain, past and present. We ended with a sense that the people of this island were beginning to both reshape the oil majors and the nation’s future…In the ruins of oil world the new is being built.”