Explainer: What the COP26 and G7 promises to stop funding fossils in 2022 mean for climate and communities

39 countries and institutions signed a joint commitment to end any support for fossil fuels flowing abroad by the end of 2022, and in its place prioritize finance for clean energy. Recently the G7 reaffirmed their commitment and were now also joined by Japan, the only G7 member who hadn’t signed on. Here’s what that means.

At COP26 in November 2021, 39 countries and institutions signed a joint commitment on “International Public Support for the Clean Energy Transition” (the Glasgow Statement) to end any support for fossil fuels flowing abroad by the end of 2022, and in its place prioritize finance for clean energy. The signatories of this commitment — called “the Glasgow Statement” here for short — included some of the largest historic providers of international public finance, including Canada, the United States, Italy, and Germany.

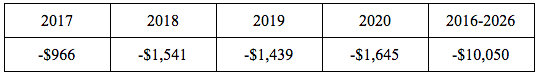

Building on this momentum the G7 Environment, Climate, and Energy Ministers made a near-identical commitment in their May 2022, Communiqué. This meant that six G7 members reaffirmed their commitment to the Glasgow Statement, and were now also joined by Japan, the only G7 member who hadn’t signed on, and the world’s second-largest provider of public finance for fossil fuels. Together, these statements have the potential to shift USD 39 billion a year of public finance from fossil fuels to clean energy.

These commitments set a historic precedent as the first international political commitment that not only addresses ending public finance for coal but also includes ending funding for oil and gas. This means that signatories’ international public finance would be more aligned with climate science, which makes clear that there can be no new investments in coal, new oil or gas supply, or liquified natural gas (LNG) infrastructure to maintain a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

However, soon after the meetings in May, there were already signals of backsliding on their commitments from G7 countries: Japan claimed it could continue financing upstream oil and gas projects despite the G7 pledge, and Germany’s Chancellor Scholz stated that Germany wants to “intensively” pursue gas projects in Senegal. Despite pressure from civil society, in late June, the G7 leaders’ statement added new loopholes to the commitment to support investments in liquefied natural gas (LNG) as “appropriate as a temporary response” in response to Russia’s War in Ukraine.

This backsliding at the G7 has been met with widespread backlash from climate activists and civil society organizations who have argued that the only ethical response to the energy crisis caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine is to ‘end our addiction to fossil fuels’ and accelerate the just transition to clean energy. Many of the same organizations have also written letters to signatory countries with recommendations for effective implementation of the commitments.

International climate agreements have been plagued by wealthy countries’ broken promises since they began 30 years ago. The very near-term target in the Glasgow Statement, coupled with its potential shift of deadly fossil fuel support to two of the areas that have been stymying negotiations the most — climate finance and loss and damage — mean it could break from this past and spur much-needed action at COP27. But for it to have this outsized impact, signatories have to get serious about meeting their end-of-year target.

Why the focus on public finance?

Not only do public finance institution investments total $2.2 trillion annually, but they are also uniquely placed to kickstart a just, transformative, and rapid transition to clean energy. Why? Because public finance institutions can give below-market rates, extra technical advice, longer loan periods, government-backed guarantees, and other benefits, they are often needed to get large infrastructure projects built. If used well, public finance institutions can play a central role in supporting public transit, building retrofits, decentralized renewable-friendly grids, community-owned solar, and other key infrastructure needed to build a just transition in line with 1.5°C. But that cannot happen if these institutions continue investing in fossil fuels. And as our graph below illustrates, this remains the case for a number of Glasgow signatories.

Figure 1: Glasgow signatories’ international public finance for fossil fuels, renewable, and other energy, annual average 2018-2020, USD billions. Includes high-income signatory countries or institutions with more than $100 million a year in known energy finance. The Data is from OCI’s public finance database: energyfinance.org

With 5 months left to turn the Glasgow Statement pledge into concrete action, now is a critical time to ensure countries get on track to end international public finance for fossil fuels in time for the 2022 deadline. There is still a risk that bad-faith implementation of the Glasgow statement could leave loopholes for continued fossil fuel support, fail to accelerate a just transition to clean energy, and allow indirect and domestic finance to continue funding fossil fuels – and civil society will be holding them accountable to their commitment.

Turning Pledges into Action, a new report from OCI, the International Institute for Sustainable Development, and Tearfund shows countries that promised to stop financing fossil fuels overseas are not on track to meet their 2022 deadline. We found that halfway through the allotted period, countries are a long way from bringing in the necessary policies to stop international public finance of fossil fuels. Weak implementation was already a risk when the commitment was signed, but it has only increased because of Russia’s war on Ukraine and the energy price crisis, which the fossil fuel industry has taken advantage of to both falsely blame climate policies for the high prices and put more oil and gas expansion back on the table.

Thankfully, the report also has good news: the Glasgow Statement could accelerate a green energy revolution in low-income countries with up to $39 billion a year of international public finance going to renewables – if signatories stick to their promise. It highlights that this would not only help meet climate and clean energy goals but also serve development and energy security objectives.

Are countries meaningfully delivering on their COP27 and G7 promises?

Canada: In Canada, a cabinet minister has suggested that they may not meet their timeline for phasing out fossil fuel finance from their Export Credit Agency, Export Development Canada (EDC), which between 2018-2020 was responsible for 39% of all Glasgow signatories’ financing to fossil fuels. EDC recently released its 2030 climate targets, which do not end financing for fossil fuel projects, but commit only to a paltry 15% reduction in its financing portfolio related to upstream oil and gas production by 2030.

Germany: Despite signing on to the Glasgow Statement, Germany Chancellor Scholz has since stated they want to “intensively” pursue gas projects in Senegal. African climate activists have been vocal that pursuing new fossil fuel investments would only further lock in climate catastrophe and stranded assets, and that investments need to instead be made in “distributed renewable energy systems that won’t poison our rivers, pollute our air, choke our lungs and profit only a few.”

Japan: After the G7 ministerial pledge, the Japanese government claimed it could continue public support for oil and gas upstream developments.

Netherlands: The Dutch government was supposed to present its new policy ahead of the summer, but after the G7 weakened their stop funding fossils commitment, the Netherlands decided to delay the publication of their policy until the fall.

Belgium: In July, the Belgian export credit agency (ECA), Credendo, published its energy transition policy to implement the Glasgow Statement. Though the policy introduces new restrictions on fossil fuel finance, loopholes mean that the policy does not match the COP26 commitment: these allow continued financing for gas-fired power up until 2025 and financing for existing oil and gas fields approved before 2022 if certain conditions are met.

For a livable planet: Expanding the reach and impact of the Glasgow Statement

While some signatories are behind in turning their commitments into policy, the good news is several governments and development finance institutions have adopted policies that are compatible with and in some cases even go beyond the requirements of the Glasgow Statement. These policies show other signatories that achieving the Glasgow Statement commitment is possible, and provide examples of good practice on how it can be done. This includes Denmark and the United Kingdom along with the French Development Agency, and Swedfund, who have all enforced a near complete or full ban of new support for fossil fuel projects, including unabated gas-fired power plants.

Other signatories must follow suit to meet their own commitments and work to expand the scope and impact of the Glasgow Statement by:

With 5 months left until the end of the year and only 4 months left till COP27 in Egypt, signatories clearly have lots of work to do. Successful implementation could mean a transformative boost towards a just energy transition, but to realize this potential, countries must implement their pledges with integrity and not introduce loopholes under the guise of energy security when this undermines rather than supports energy security. Instead, they must fully redirect their public finance for oil and gas to clean energy finance, which would more than double international clean energy finance from USD 18 billion a year to USD 46 billion. As shown over recent weeks, CSOs and climate activists are ready to hold countries accountable to their commitments and will not allow them to sacrifice a livable planet for all by backsliding on their climate goals.

¹ Indirect finance refers to finance provided through financial intermediaries, technical assistance, and the policy-based lending of some multilateral development banks. It is of growing concern as it is likely that increasing amounts of public finance for fossil fuels are provided this way. To avoid this trend, the Glasgow Statement should be expanded to indirect finance as well.