New climate research predicts “disaster for many low-lying cities”

It is no longer a question of “if” the unthinkable happens, but a question of “when”. And the “when” could happen sooner than you think. For decades now climate scientists have been worried about what happens if the vast West Antarctic ice sheet melts.

It is no longer a question of “if” the unthinkable happens, but a question of “when”. And the “when” could happen sooner than you think.

It is no longer a question of “if” the unthinkable happens, but a question of “when”. And the “when” could happen sooner than you think.

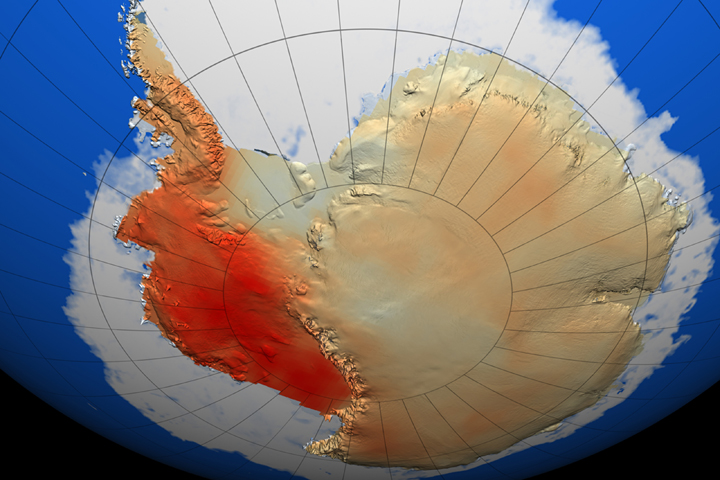

For decades now climate scientists have been worried about what happens if the vast West Antarctic ice sheet melts.

The melting of the ice-sheet, which is greater than the size of Mexico, has always been seen as somewhat of a doomsday scenario as it has to the potential to rise sea level by several metres. This is due to the fact that much of the ice-sheet sits on the ground, rather than floats.

Scientists have known about the threat for decades. As the respected British environmental journalist, Paul Brown, wrote twenty years ago in his book Global Warming – can civilization survive?: If the West Antarctic Ice sheet melted “it could add between 4 and 7 m (13-23 feet) to sea level rise … such figures appear to create the potential for a series of large-scale catastrophes.”

By its very nature, any sea level rise of this nature would be catastrophic – wiping out most coastal cities and low-lying areas.

Maybe because the thought is so unthinkable, it has been easy to dismiss. The deniers and climate sceptics have long responded that this kind of speculation was scaremongering.

The other source of comfort is that even in their worst nightmare scenarios, scientists thought that this would happen over a period of hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

But not any more.

Scientists now believe that that the vast ice sheet is melting much more quickly than before, in part due to rising air temperatures as well as rising sea-temperatures.

Yesterday a paper, published in the prestigious journal Nature predicted that “Antarctica has the potential to contribute more than a metre of sea-level rise by 2100”.

Added to melting ice in other regions, this means that sea level rise could be some five to six feet higher by the end of this century.

As the New York Times reports: “That is roughly twice the increase reported as a plausible worst-case scenario by a United Nations panel just three years ago, and so high it would likely provoke a profound crisis within the lifetimes of children being born today.”

If this is not mind-blowing enough, the scientists add that sea level rise could be “more than 15 metres by 2500, if emissions continue unabated”.

It is worth reading the next two sentences twice from the Times, allowing them to sink in:

“The long-term effect would likely be to drown the world’s coastlines, including many of its great cities .. New York City is nearly 400 years old; in the worst-case scenario conjured by the research, its chances of surviving another 400 years in anything like its present form would appear to be remote.”

For those of us who have written about climate change for decades, we have often wondered when the tipping point will come that spurts governments into radical and urgent action.

Great storms have come and gone, cities have already been plunged under water, destructive droughts have killed millions, and yet we carry on roughly as normal. Yes, renewables are gaining hold, but not nearly fast enough and governments still subsidise fossil fuels to the tune of billions.

The obvious response to my last paraghraph is to argue that we are not carrying as normal, that only a few months ago that Governments signed an historic agreement to tackle climate change in Paris.

Before that lulls you into a false sense of security, the deal is not nearly enough to save the West Antarctic ice sheet. It does not go anywhere far enough to reduce carbon emissions to the degree necessary.

“The bad news is that in the business-as-usual, high-emissions scenario, we end up with very, very high estimates of the contribution of Antartica to sea-level rise” by 2100, Professor Robert DeConto, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who led the work, tells the Guardian. “This [doubling] could spell disaster for many low-lying cities.”