Of Memory and Power

Remembering past struggles against oil: Ida Tarbell, Mohammed Mosaddegh and Ken Saro-Wiwa.

Today, 10 November 2018, is the 23rd anniversary of the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight fellow activists who stood up to Shell’s destruction of their lands. I am thinking lots about their struggle today, and decided to share this speech I gave at the Seeding Climate Justice conference in Maputo, Mozambique, in May. It’s about how lessons from past struggles shape our work today.

The International Politics of Oil

I’ve been invited to talk to you about the international politics of oil. Many of the people in this room have experienced the politics of oil directly, in their communities where oil companies operate. I live in London, a centre of corporate power for the oil industry, and I came here mainly to learn. But I will share some international and historical perspectives, in the hope of contributing to the conversation.

Very often when people talk about the politics of oil, they talk about the struggles for power and wealth, among people who are already powerful: presidents, kings, and chief executives. To me, the politics of oil is more about the struggle for justice against power and wealth.

The Czech author Milan Kundera wrote that the struggle of people against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting. In this presentation, I am going to remember three movement leaders who stood up to the oil industry, and who continue to inspire our work in Oil Change International. I am going to describe how their struggles shine light on the politics of the oil industry. And after that, I am going to talk about climate change, and what we can learn from past struggles to inform our work today.

* * *

Ida Tarbell was an American teacher, a historian and a feminist. While recording the contemporary social situation, she became one of the world’s first investigative journalists. In the early years of the Twentieth Century she meticulously catalogued the business practices of Standard Oil, the world’s largest oil company.

Since the origins of the modern oil industry in Pennsylvania in the late 1850s, Standard Oil had exemplified the era of the robber barons, which Americans were increasingly mobilising against. Standard accumulated oil assets, especially refineries, railroads and pipelines until it cornered the market, and used its resulting dominance to drive rivals out of business, squeeze suppliers, and deprive governments of revenue.

Tarbell gathered hundreds of documents revealing these practices. These documents, and her subsequent book, led to the Supreme Court declaring Standard Oil an illegal monopoly and ordering its breakup into several smaller companies.

Since then of course, the constituent companies have grown, and the two largest, Exxon and Mobil, re-merged in 1998. The business practices Tarbell exposed are all too common in the oil industry. For example, today Shell and Eni are being prosecuted for alleged payment of bribes of $1 billion in Nigeria. But Tarbell’s work helped create the public distrust of oil companies that today makes such prosecutions possible.

* * *

As the oil industry in the 20th century expanded beyond the United States, it did so through long-term contracts, which frequently gave exclusive rights to extract a whole country’s oil, for a period of up to 75 years. The companies would make all the decisions, including on what minimal amount of the revenue to give to the host government. During the 1930s and 1940s, people of oil-producing countries increasingly organised against these contracts.

As the oil industry in the 20th century expanded beyond the United States, it did so through long-term contracts, which frequently gave exclusive rights to extract a whole country’s oil, for a period of up to 75 years. The companies would make all the decisions, including on what minimal amount of the revenue to give to the host government. During the 1930s and 1940s, people of oil-producing countries increasingly organised against these contracts.

At the time, almost the entire world oil market outside the Soviet bloc was controlled by a handful of companies: Exxon, Shell, BP, Mobil, Chevron, Texaco, and Gulf. A 1952 U.S. Senate report described them as ‘the international petroleum cartel.’

Mohamed Mosaddegh was a lawyer and a democrat, typical of the nationalist intellectuals of the age. He was elected prime minister of Iran in 1951, on the back of popular resistance against the 60-year contract held by BP.

In one of his first moves in office, he cancelled the contract, and nationalised BP’s assets. The oil industry responded by boycotting Iranian oil, sending the country rapidly towards bankruptcy. Still, efforts by the Shah – a British client – to remove Mosaddegh were unsuccessful, due to mass popular mobilisation in support of the prime minister and his oil policy.

But in 1953, the US and British governments, through the CIA and MI6, sponsored a coup in Iran. The coup succeeded in deposing Mosaddegh, restoring autocratic rule, and bringing back the Western oil companies, although now including American companies as well as BP.

The nationalisation of Iran’s oil served as an inspiration for neighbouring Iraq’s law in 1961, which significantly restricted the foreign oil companies’ contracts. That led in turn to nationalisations of the oil industry throughout the Middle East, North Africa and elsewhere in the 1970s, and in many other countries led to the country itself taking a fairer share of the revenues. In 1962, the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on Permanent Sovereignty Over Natural Resources, a defining moment in moving beyond the colonial era, giving countries economic as well as political independence.

While the multinationals no longer controlled most of the world’s oil, they deepened their power in the countries where they still operated. And just as in their early years, the companies did this through contracts. Their production rights today are for 30 or 40 years rather than 60 or 70, and they do not cover entire countries. But they again take away countries’ sovereignty.

A phrase that the oil industry uses in discussing contracts is the “obsolescing bargain” – the bargain that goes out of date. What this means is that in a new oil country, companies sign up oil contracts with a government that doesn’t have experience of oil, and often has less technical expertise than the companies’ lawyers and accountants. Perhaps ten or twenty years later, once the oil is flowing, the country has some experience and some expertise, and realises it got a bad deal. But the contract has fixed the terms. The contract locks in the situation at the time of signing, essentially holding back the country from developing. This may be an issue today in Mozambique with the dash to gas.

To prevent developing economies trying to update the terms, any disputes are heard not in the country’s courts but in international investment tribunals, often in secret. Those tribunals can order governments to pay out, and allow the companies to seize the country’s assets if it doesn’t.

Usually these contracts require governments to compensate any profits a company claims to have lost as a result of new laws or regulations – even those that protect the environment or the public interest.

* * *

I’m not going to say very much about Ken Saro-Wiwa, because Mike will tell us about oil in Nigeria in detail.

The oil operations in the Niger Delta are, in my view, emblematic of the environmental racism of the oil industry. Companies like Shell have operated there in a way that they would not do in Europe or the United States. Frequent spills from poorly-managed oil facilities have caused massive contamination of ground and water, decimating livelihoods and food security. Although gas flaring has been illegal in Nigeria since 1984, it continues, often within yards of people’s homes.

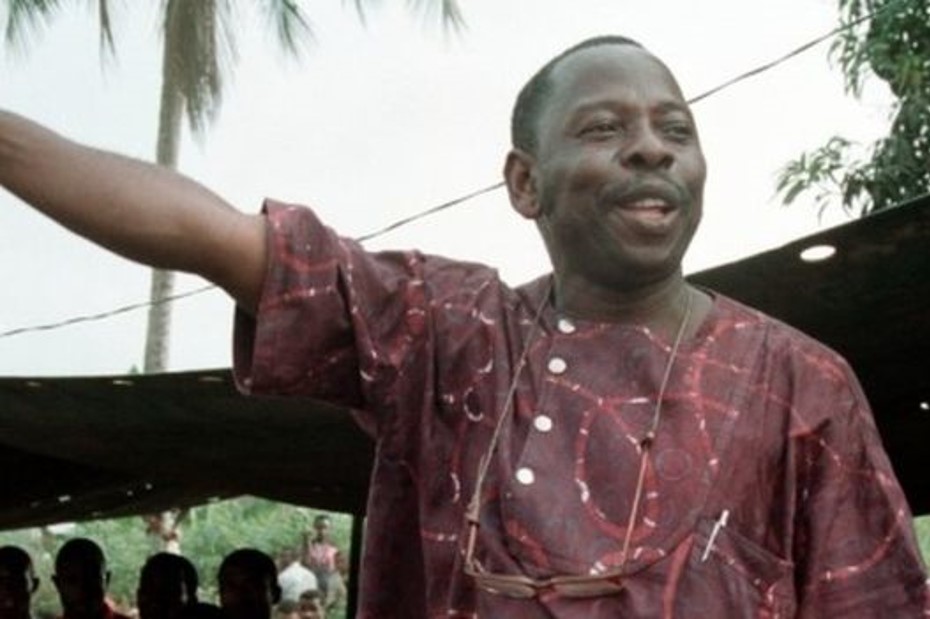

In the early 1990s, Ken Saro-Wiwa, a well-known writer, led a nonviolent campaign by the Ogoni people against the environmental devastation caused by Shell and other oil companies. At one protest in 1993, 300,000 Ogonis, about 60 percent of the whole population, came out into the streets. They forced Shell to withdraw from Ogoniland.

But the Nigerian government, which was then a dictatorship, responded by militarising the region, terrorising its population and killing numerous people. Recent research by Amnesty International has uncovered documents showing Shell’s complicity in this violence. Ken Saro-Wiwa was framed for a murder and arrested in 1994. The following year, the dictatorship executed him along with eight other Ogoni leaders.

Saro-Wiwa was in prison when I first learned of his struggle, and pressing for his release was the first campaign I – as a young student – got involved in. Tragically, we were unsuccessful. But his leadership, his courage, and his sacrifice were what made several of us who are now in Oil Change International decide to dedicate our lives to fighting Big Oil, and continue to inspire movements against corporations around the world.

* * *

Tarbell, Mosaddegh, and Saro-Wiwa highlighted three themes that lie at the heart of the politics of oil: the abusive power of corporations, the industry’s restriction of sovereignty and democracy, and the devastating cost of oil operations to communities and nature. We see in their stories the violence that lies at the heart of the oil industry.

But this history also shows us how our movements have advanced. Tarbell fought the excessive power of corporations, and their abuse of that power. Mosaddegh drove out those corporations, fighting for sovereign control over a nation’s oil resources. And Saro-Wiwa returned power to communities themselves, enabling sovereign decisions not only over who controls the oil, but over whether oil should be extracted at all.

And this brings me to climate change.

* * *

So far there has been about one degree Celsius of warming since pre-industrial levels. The world is already experiencing dangerous climate change, through drought, storms and floods. Many of the worst impacts are felt in Africa, by people who did the least to cause the problem.

As Dipti explained yesterday, achieving the Paris goals requires an urgent phaseout of fossil fuels. Just seven more years of emissions at the current rate will take us to 1.5 degrees of warming.

Our research in Oil Change International has found that the oil, gas and coal in the fields and mines that are already in production – where the infrastructure has been built and the capital invested – would be enough to take warming significantly beyond two degrees. The oil and gas alone would take us past 1.5 degrees.

Nnimmo said yesterday that the world has too much reserves, and the industry must stop exploring for more. I agree, but I will go one or two steps further. The industry must stop not just looking for but also developing new fields and mines, and building new pipelines, ports and rail lines. And much of what is already in operation must be closed down long before the end of its economic life.

Clearly the fastest shut-down must happen in the richest countries, where it will be least disruptive. Shamefully, yesterday the Canadian government – which likes to claim to be a climate champion – announced that it would buy out a pipeline to make sure tar sands extraction can keep growing, because it claims it would be too disruptive to stop expanding. Bear in mind that oil accounts for about 2 per cent of Canada’s GDP, compared to say, Angola, where it is more than 40 percent. The movements in Canada are working hard to make sure that pipeline does not get built.

There must also be a just transition, where the workers and communities who are dependent on the fossil fuel industry are put at the centre of shaping its wind-down, and provided with the resources to sustain livelihoods and social protection.

Northern countries owe an enormous climate debt to poorer countries, both because they have caused climate damages, and because they have left no atmospheric space for those countries’ development. But if we are to avoid going beyond 1.5 degrees or 2 degrees, no new fossil fuels can be developed anywhere. What does it mean for permanent sovereignty over natural resources, where one country’s sovereign right to extract deprives other countries of their sovereign rights to the atmosphere or ecosystems?

And what of the companies? Research by the Climate Accountability Institute has shown that one in nine of the additional carbon atoms in the atmosphere where extracted by just four oil companies: Shell, Exxon, Chevron, and BP. One-ninth of climate change is caused by those companies.

Like Canada, Shell also claims to be a climate leader among its peers, even while it expands its oil production. It recently published two reports to try to justify this claim. In the first, it said that the only way the Paris goals could be met would be by someone inventing a technology to suck carbon out of the air, because Shell said oil and gas consumption and production would continue at current levels until the 2050s, and only start to be reduced after that.

In its second report, Shell argued that it is progressive on climate change because it will avoid having any ‘stranded assets.’ It argued that the responsibility for preventing dangerous climate change lies with governments and consumers; Shell’s own responsibility is only to ensure it remains profitable while those changes occur. It’s as if I was a serial burglar of houses, and told the court that I should be found not guilty because although I will keep burgling until there are no houses left to rob, I will make sure I have found myself a new livelihood by that time.

When oil companies look at Africa, they do not see the human costs caused by their products and operations, and certainly do not take responsibility for them. They see something like this map (which was compiled by our friends in OpenOil): more opportunities to extract yet more oil and gas.

I believe the solutions come neither from Northern governments nor from oil corporations. Our success in stopping climate change will come from the actions of social movements, in both North and South. And I believe that in the 20 years I have tackled the impacts of the oil industry, our movements are stronger now than at any time in that period.

Last year, a group of civil society organisations met in an oil-threatened island in Norway and drafted the Lofoten Declaration, which states that “it is the urgent responsibility and moral obligation of wealthy fossil fuel producers to lead in putting an end to fossil fuel development and to manage the decline of existing production.” So far, it has been signed by more than 500 organisations.

We are starting to see successes with governments declaring an end to oil licensing: France, soon Ireland, and New Zealand for its offshore. Some Southern governments are joining too, including Costa Rica and Belize. This trend will grow, and now movements are pushing for this trend to extend to larger oil producers, such as California, Canada and Norway. And last December, after many years of campaigning, the World Bank announced that it would stop financing oil and gas extraction.

As for me, I continue to draw strength from the achievements of those who came before us, like Ida Tarbell, Mohammed Mosaddegh, and Ken Saro-Wiwa. I am inspired by the struggles we have heard about here. We have a huge challenge, but I believe we will win.