Very Tasty Squids, The Climate Crisis, and Japan’s Fossil Fuel Expansion in Indonesia

Conservation zones are not meant to be industrial sites, let alone home to a coal-fired power plant that pollutes the sea and destroys the surrounding environment. Yet, in pursuit of development, the local government altered the official conservation maps—twice—to smooth the way for the Batang coal plant.

“Go ahead, let’s eat. The squids are fresh from the ocean—I just caught them a couple of hours ago.”

Haryono, we call him Pak Har, wasn’t exaggerating. The squids were incredibly fresh and might be the tastiest I’ve ever had, especially for someone who lives in the big city. They were delicious. Served with hot rice, tempeh, sambal, and krupuk (rice crackers), it was easily one of the best lunches I’ve had in a long time.

Pak Har and his family kindly hosted us during our stay in Roban Timur Village, Central Java, Indonesia. There were seven of us—campaigners from The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI) National, WALHI Central Java, Oil Change International / Fossil Free Japan Coalition, and youth activists from Central Java—who ‘occupied’ his house and turned the living room into our sleeping area.

Pak Har and the Roban Timur community welcomed us with open arms. They gave us a place to sleep and served us delicious meals. Each morning, we would sit on the beach with a cup of coffee, soaking in the calm. Most importantly, it was deeply inspiring to spend time with a community that remains hopeful and resilient, despite the heavy impacts of fossil fuel expansion. Around the village, we could still see remnantsof their brave resistance against a Batang coal power plant project that threatens to destroy their environment and livelihood.

We were here to join the community to celebrate the Sedekah Laut procession, an annual tradition to express gratitude for the sea’s abundant catch, and to pray for safety and blessings in earning a living from the ocean. It was a beautiful celebration, though unfortunately, we also witnessed firsthand the damaging impacts of fossil fuel expansion on nature and people’s livelihoods.

Japan is driving these damaging impacts on Indonesian communities like the Roban Timur Village by financing fossil fuel projects. It remains one of the biggest threats to a just and equitable energy transition in the region. It is now among the largest financiers of fossil fuels, driving gas expansion in Indonesia and around the world.

Despite its commitment under the G7 framework to end public financing for fossil fuels, Japan continues to invest in and promote fossil gas as a so-called “transitional fuel.” Between 2020 and 2022, Japan spent an average of at least USD 6.9 billion annually on gas, coal, and oil, and it became the world’s largest provider of international public finance for gas—averaging USD 4.3 billion per year over that period.

Love Beach… May Be Gone Too Soon…

Pantai Cinta. Means Love Beach in English.

We would start each morning here, sipping coffee as we watched the sunrise.

The climate crisis, driven by fossil fuels, is a harsh reality here. Both the climate crisis and the Batang coal power plant threaten the community’s livelihood, the surrounding environment, and the very existence of the village.

“Roban Timur is losing two to three meters of land every year due to coastal abrasion,” said Fahmi Bastian, Director of WALHI Central Java. “Everything changed when the Batang began the main construction in 2016, and then when the coal-fired power plant became commercially operational in August 2022. The ocean is polluted, the environment degraded, the coastline eroded—and the income of fisherfolk has declined.”

Roban Timur sits between two rivers: the Roban River and the Kaliurang River. According to Fahmi, sedimentation from these rivers could also alter ocean currents. “There are several contributing factors, whether it’s the power plant, river sedimentation, or extreme weather events in the Batang waters.”

One of the clearest impacts of the climate crisis is erratic weather. Normally, the ‘musim baratan’ or west wind season, along the North Coast (Pantura) lasts from November to February. “But recently, wave heights in Roban Timur have been unusually high. That’s clearly a weather anomaly and a symptom of climate change.”

Fahmi suspects that the Batang coal power plant is accelerating coastal erosion and devastating the fishing community’s living space. The sea is polluted, marine ecosystems are damaged, and fisherfolk’s access to key fishing areas is increasingly restricted. Coal dust and runoff from the plant smother coral reefs and drive away fish that once thrived there, while waste from dredging clouds shallow waters, blocking sunlight from reaching reefs and seagrass beds. A two-kilometer jetty cuts directly through a coral conservation zone and prime fishing ground, obstructing traditional routes and forcing boats into more dangerous and costly waters.

All of the things that campaigners warned about the Batang Coal power plant have become a reality.

Fisherfolk now spend more hours at sea, burn more fuel, and face rougher conditions to catch fewer fish than before. Traditional nets are often damaged by coal debris or snagged on submerged waste, adding another financial burden. These combined pressures have turned once-abundant fishing zones into empty, hazardous waters, robbing the community not only of income, but also of a way of life passed down through generations.

“Almost 100 percent of Roban Timur community is fisherfolks. We depend on the oceans, and now the situation is hard,” said Wahyudi, who is the leader of Roban Timur Fisher Group.

“Before the power plant, I could reach the fishing grounds in just 30 minutes,” said Wahyudi, a local fisherman. “I only needed about 10 liters of diesel, and the catch was decent.”

But everything changed after the Batang coal plant’s construction began in 2016. Wahyudi—along with many other fishers—was forced to go further out, as the area that was once a “paradise” for fishing is now off-limits. That area, known as Karang Preketek, has been claimed as part of the plant’s operational zone.

Today, Wahyudi must travel around 12 nautical miles—about two hours—to find viable fishing grounds. The operational costs are much higher, and the catch is lower. “Our livelihood was impacted, even from the beginning of the construction phase.”

Protected, then no more

When construction of the coal-fired power plant began, the local fisherfolk were already feeling the impacts.

“Due to the improper disposal of dredged sediment, rocks, and other construction waste, many of our fishing tools were damaged. And we received no compensation from the company,” explained Abdul Halim, a respected community leader in Roban Timur.

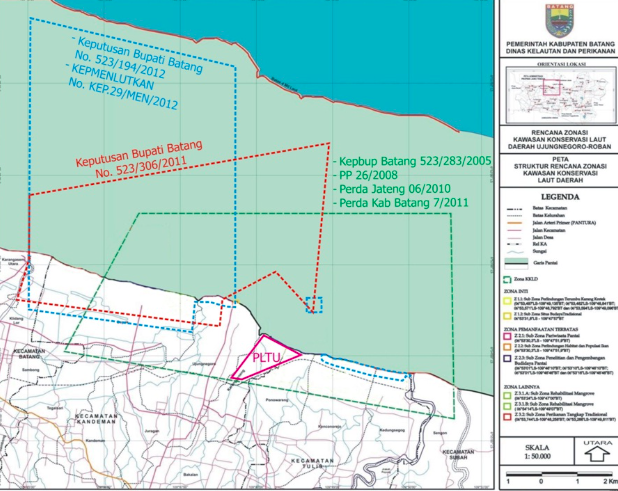

But environmental and community rights had been ignored long before construction even started. The Ujungnegoro–Roban coastal area was originally designated as a marine conservation zone—a status backed by strong legal protections.

As a legally protected marine conservation zone, no project should be allowed that risks damaging the ecosystem. And yet, in a move to pave the way for the coal power plant, these protections were conveniently rewritten.

Despite its protected status under both the Regent’s Decree and national spatial planning regulations—including Government Regulation No. 26 of 2008 (Annex VIII, Item 313)—the Batang coal plant was still built in this conservation zone. The area, known for its rich coral reefs and marine biodiversity, was once deemed worthy of protection.

It couldn’t be clearer. Conservation zones are not meant to be industrial sites, let alone home to a coal-fired power plant that pollutes the sea and destroys the surrounding environment. Yet, in pursuit of development, the local government altered the official conservation maps—twice—to smooth the way for the Batang coal plant.

Japan’s Dirty Expansion

All of these risks to the community’s livelihood and the environment could soon worsen, as there are plans to build a gas power plant right next to the coal power plant.

In 2024, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) uploaded 34 new MoUs under the Asia Zero Emissions Community on their website. One of the projects was an “MOU among 3 companies for Feasibility Study for development of CCGT Power Plant in Indonesia ”. Those three companies are the same old Itochu Corporation, J-POWER and PT Adaro Power.

“Japan’s fossil fuel expansion will prolong fossil fuel dependency in Indonesia and across Asia, risk derailing emissions targets, and harm frontline communities,” said Hozue Hatae from Friends of the Earth Japan.

Specifically, to a proposed gas-fired power plant project, Friends of the Earth Japan had sent an inquiry to Itochu Corporation regarding the project.

In its response, Itochu confirmed that the project is still in its initial investigation phase, not yet a full feasibility study. The company declined to disclose a timeline or share documents, citing confidentiality.

“Crucially, no consultations have yet been conducted with local communities, including farmers and fishers, despite the project being located in an area with a long history of environmental conflict and local opposition to fossil fuel infrastructure. Itochu stated that such consultations would occur ‘appropriately’ as the project progresses,” Hozue explained.

“It is also critical to ensure meaningful consultations and information disclosure with local communities to be affected by the project, in an earlier stage. The communities must not be left out from the beginning, which happened in the Batang coal-fired power plant case,” said Hozue.

False Solutions, Real Consequences

The proposed gas power plant in Batang is not an isolated project. It is part of Japan’s broader Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) initiative, which is aggressively promoting so-called “transitional” fossil-based technologies like gas, ammonia and hydrogen co-firing, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS/CCUS) across Southeast Asia.

Under the guise of decarbonization, AZEC is effectively locking countries like Indonesia into decades more fossil fuel dependence. These projects are branded as low-emission or “clean” energy, but in reality, they delay the shift to truly renewable sources, worsen climate impacts, and place the heaviest burdens on frontline communities, like those in Roban Timur.

“AZEC is not a solution, it’s a trap,” said Dwi Sawung, Energy Campaign Manager at WALHI. “It only serves to extend fossil fuel infrastructure, keeping Indonesia tied to dirty energy while communities continue to bear the environmental and economic costs.”

From polluted seas to lost livelihoods, from erased conservation zones to disappearing coastlines, the human and ecological costs of these false solutions are real and irreversible. Communities that have long protected their ecosystems are now being sacrificed in the name of energy security and economic growth, driven by foreign interests and corporate profit.

“If Japan truly wants to support a just energy transition in Indonesia, it must stop pushing technologies that only benefit its own corporations,” Dwi added. “We need real support, not more fossil fuel projects disguised as green.”