The history of carbon capture is failure after failure. $83 billion has been invested in carbon capture globally up until 2023, with over $30 billion in government funding. The results are that almost 80 percent of carbon capture projects have been postponed or canceled. According to DNV’s overview, the number of failed projects has increased in recent years.

The Mongstad scandal in Norway, where Jens Stoltenberg’s second government was supposed to finance the construction of a full-scale carbon capture plant, ended up with billions in budget overruns and no full-scale carbon capture. This led to a devastating report from the Norwegian National Audit Office and was described as critically flawed after scrutiny by the Parliamentary Control and Constitutional Committee. Such results are the norm around the world.

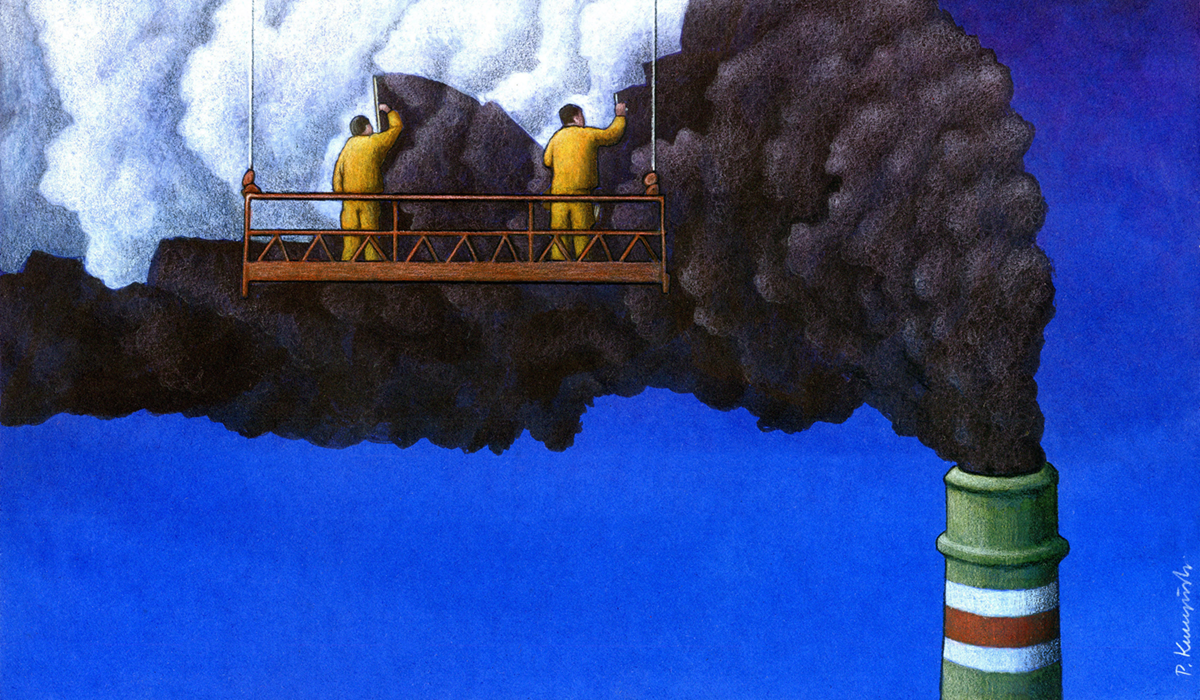

Carbon capture cannot cut nearly enough emissions. Even when carbon capture projects are completed, it is not possible to capture anywhere near 100 percent of the emissions from the facilities it is connected to. No CCS facility in the world has managed to capture more than 78 percent of the emissions from the operations it is associated with. This is despite the industry using capture rates of 90 per cent or more as standard. DNV data shows that the utilization rate (actual capture compared to capacity) globally has been only 53 percent.

The global CCS capacity, the maximum amount that can be captured and stored in the best case scenario, corresponds to only 0.1 percent of the world’s annual emissions (about 50 million tons of CO2 per year). Actual capture and storage is much less than this potential (up to 30 percent less according to one research article). In addition, we should be skeptical of the capture figures that oil companies claim. In addition to reporting incorrect figures to the Norwegian Environment Agency, Equinor had to apologize after it was revealed that they had exaggerated on their website how much CO2 had been stored at one of the company’s Norwegian carbon capture projects. The low capture figures are among the reasons why the International Energy Agency (IEA) has downgraded its expectations for carbon capture by 39 percent in the agency’s scenario for net zero emissions by 2050.

Carbon removal directly from the air, and then storing the carbon in the same way as carbon capture technology, is called DACCCS (direct air capture with carbon capture and storage) and depends on carbon capture and storage technology. This technology is even more expensive per unit of emissions than CCS, and would have enormous energy requirements that would either nullify any emissions removed (if the energy comes from fossil sources) or take renewable energy away from other uses. As a report from Cicero and WWF shows, this means that Norway’s climate goals depend largely on unproven technologies.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ranked carbon capture as the most expensive and least effective measure for the emissions cuts the world needs by 2030 to meet the 1.5 degree target. The IPCC’s scenarios with the greatest likelihood of meeting the 1.5 degree target rely less on carbon capture. While the cost of renewable energy is falling rapidly, research shows that the cost of carbon capture has not been reduced in over 40 years . A climate transition dependent on carbon capture would cost $30 trillion more than a transition based on less carbon capture and real emissions cuts. Social costs from among other things increased energy demands and more air pollution could cost up to $80 trillion more per year in scenarios that promote carbon capture and carbon removal.

Norway’s carbon capture fantasy could become a new nightmare

Norway has already provided the largest per capita subsidies for carbon capture globally. The cost framework for Longship has increased from approximately 30 billion kroner in 2025 kroner (25.1 billion in 2021 kroner) to 37.7 billion kroner, of which the state takes around two-thirds (up from approximately 20 billion to 24.25 billion kroner in 2025 kroner). The costs may increase further.

Norway’s carbon capture initiative has set unrealistic targets that cannot be met. Despite increasing subsidies, the capture rate from waste incineration at Klemetsrud has already been reduced due to technical challenges, and the capture plant in Brevik will only affect around half of the emissions from cement production. Northern Lights only has two ships with a combined shipping capacity of 16,000 tonnes of CO2, although the goal of the project’s first phase is 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 storage per year. There are only two new ships on order, but the project still aims for 5 million tonnes of CO2 storage per year in its second phase, based on European projects that are not yet ready. Experts warn that it is unlikely that enough ships can be built in the future to meet the projects’ targets. The overseas projects that will deliver CO2 are also very uncertain. One of the projects is the highly controversial bioenergy with CCS (so-called BECCS) in Stockholm, Sweden, which will burn large amounts of biomass and most likely will not lead to net emission reductions.

Beyond the government’s heavily subsidized flagship, there are no new carbon capture projects underway in Norway. 13 exploration licenses have been awarded for companies to find carbon storage space on the Norwegian shelf, but only one (Longship/Northern Lights) has led to planning/operation.

All of this suggests that Norway’s and Equinor’s hopes for a large, profitable market for carbon capture (that does not depend on subsidies) are greatly exaggerated. There is a risk that infrastructure will be built without a market existing or ever being realised. Another round of exaggerated, oversized faith in an uncertain technological solution could result in another Mongstad.